Gradual Emancipation Acts

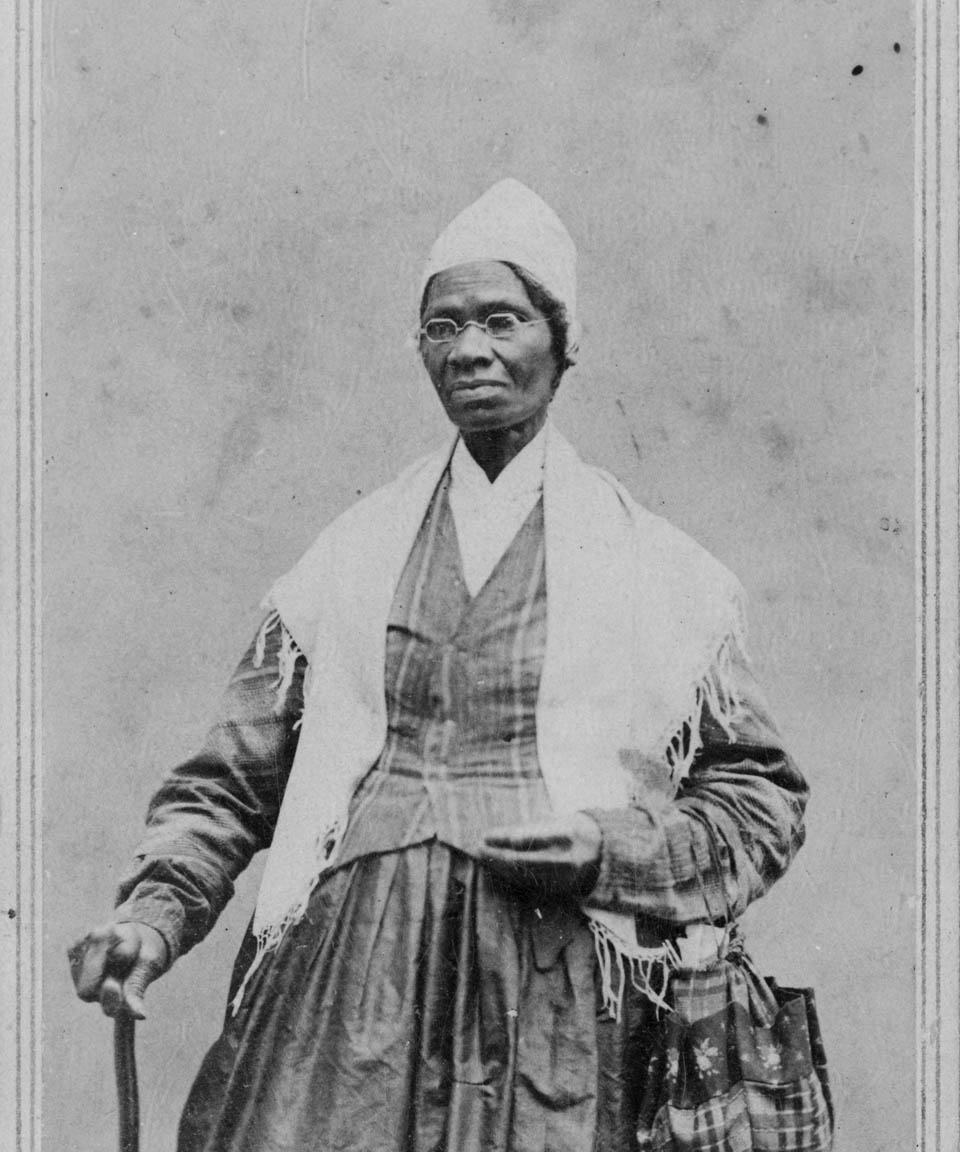

Contrary to popular belief, northern enslavement lasted nearly as long as slavery in the south. In the years surrounding the American Revolution, some enslaved individuals petitioned the courts to end slavery. Others fought in the war, having been promised freedom by British or American forces. Each state debated how to reconcile Revolutionary-era ideas about liberty with the economic fact of slavery.

Slowly, northern states began moving toward gradual emancipation, with each state establishing its own path to abolition. These efforts prioritized the economic well-being of enslavers, giving them time to recoup the financial loss of their captive workforce. For the enslaved population, freedom was painfully slow to arrive.

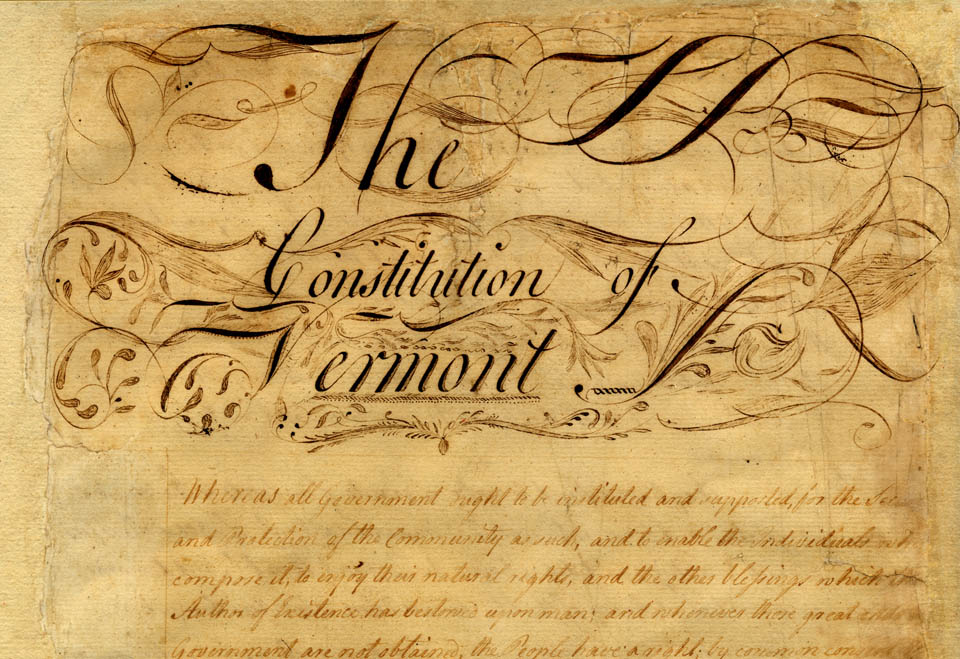

Vermont’s Constitution of 1777 banned slavery, but only for enslaved adults, not children. Additionally, some white residents of Vermont disregarded this ban. The 1790 Federal census included 16 enslaved people in Vermont. Lucy Allen Hitchcock, a daughter of Vermont patriot Ethan Allen, held two enslaved women in Burlington from 1835 until her death in 1842. Even if these women had been aware that slavery had been banned in Vermont, it was doubtful that they would have risked protesting their treatment.

Since the 1760s, enslaved people had petitioned the Massachusetts courts for freedom, but these petitions did not alter the legality of slavery there. However, after the State Constitution of 1780 was passed, several lawsuits caused the courts to reexamine the constitutionality of slavery. In 1783, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled that enslavement was incompatible with the new state constitution, but slavery continued in the state until at least 1795. Enslavement in Massachusetts quickly declined, but was not formally abolished until the passage of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.

In 1780, Pennsylvania became the first state to adopt a gradual emancipation act. It stated that any child born of an enslaved mother would be freed at age 28. While people enslaved in Pennsylvania before 1780 would not be freed, newly arrived enslaved individuals were to be emancipated after six months.

From 1790 to 1800, while the nation’s capital was located in Philadelphia, President George Washington routinely cycled enslaved laborers between there and Mt. Vernon to get around this law.

In 1840, the Pennsylvania census still listed 64 enslaved individuals. Complete legislative abolition of slavery ocurred in Pennsylvania in 1847.

Connecticut’s gradual emancipation act followed the Pennsylvania model. All children born to enslaved mothers after March 1, 1784, would be freed after a 25-year “indentureship.” Any enslaved person born before March 4, 1784, would remain enslaved for life.

The 1800 census listed nearly 1,000 enslaved men, women, and children in Connecticut, a figure that was reduced to seventeen by 1840.

In 1848, 13 years before the start of the Civil War, the Connecticut legislature passed a bill abolishing slavery within the state.

Rhode Island’s 1784 gradual emancipation act was similar to that of its neighbor, Connecticut.

Originally, the length of indentureship in Rhode Island was set at 18 years for females and 21 years for males, but in 1785, the legislature amended the act to 21 years for both sexes.

By 1810, however, there were still more than 100 enslaved individuals counted in the Rhode Island census. Rhode Island officially abolished slavery in 1843.

New Hampshire, like Massachusetts, relied on court interpretations of its constitution to determine the legality of slavery in the state.

New Hampshire’s 1783 constitution did not mention slavery, nor did the state legislature pass an emancipation act. As of the 1790 census,158 enslaved men, women, and children were listed in the state.

Slavery was not abolished in New Hampshire until 1857.

New York had the largest enslaved population of the northern colonies, and a gradual emancipation act was not passed until 1799. This act ensured that all residents born on or after July 4, 1799, would be free, but those born to an enslaved mother would serve an indentureship of 25–27 years. However, any enslaved person born prior to July 4, 1799, remained enslaved for life. In 1817, New York amended this law, stating that slavery would be abolished on July 4, 1827, for all New York residents. Despite this, enslaved laborers were still listed on the New York census as late as 1840.

Between 1790 and 1800, New Jersey was the only northern state to increase its enslaved population. Gradual emancipation in New Jersey began on July 4, 1804, but only for children born of enslaved mothers and after a 24-year indentureship.

On the eve of the Civil War, New Jersey’s 1860 census still listed 18 enslaved “apprentices for life.” Although the last enslaved person in New Jersey died in 1861, the state did not outlaw enslavement until the 13th Amendment to the Constitution took effect in 1865.

Slavery in New Jersey lasted just as long as slavery in the southern states.

It took between 12 and 74 years for states in the North to end slavery—an agonizingly slow process for those who were enslaved. Each state’s laws were designed to protect the wealth of enslavers by providing decades of additional unpaid labor before freedom was granted. Little or no provisions such as land or back pay were granted to the newly freed men and women. For many, freedom in the North meant the freedom to remain poor and at the bottom of the social order.