More Stories About Community

Despite the fact that African captives were taken by force to the American colonies, elements of their diverse cultures survived the horrific journey, including storytelling, body decoration, music, and foodways. These traditions continued in the colonies, and provided a way for enslaved Africans to maintain ties to their ancestral homes and establish connections with other enslaved people. While the origins of these traditions may not be remembered today, they were elemental to the formation of American culture.

This blending of African and European cultures was integral to Pinkster, the Dutch celebration of Pentecost that became an important holiday for enslaved people throughout the Hudson Valley. Pinkster provided the enslaved community with an opportunity to reunite with loved ones while celebrating traditional African dancing, drumming, and storytelling. Pinkster’s popularity as an African American cultural event eventually became its downfall. By the end of the 18th century, enslavers worked to suppress such demonstrations of traditional culture, fearing that they would lead to conspiracies and revolt. By 1811, New York had banned all Pinkster celebrations.

The African names of enslaved people were often excluded from written history, or anglicized by enslavers. However, the names of the enslaved often provide cultural clues as to the origins of their bearers. The Akan people gave their children Kra-din, or “day-names,” after the day they were born. “Kwaku” was the name for a boy born on a Wednesday, and it was often misinterpreted as “Quack” or “Quake.” Other seemingly Western names such as “Jack” and “Billy” could have been adapted from the Igbo “Cheque” or BaKongo “Vili.”

These traditional names were another way for enslaved individuals to remain connected to their culture.

The variety of African ethnicities and languages in many northern colonial cities led to an infusion of African words into the American vocabulary. For example, the word tote comes from tota, a Kikongo word meaning to carry. Kook, a foolish person, has its origins with the Bantu word kuku. Phony is from foni, a Mandingo word that means false or deceptive. Gumbo is from the West African thick stew called kingombo, and the term okay can be traced to several West African languages that use o-ke or waw-ke as the word for yes or all right.

Some African captives practiced ritual scarification as a way to continue their own cultural traditions. Advertisements for the return of Nell, who self-emancipated multiple times, described her as having “three Diamonds on her face,” one on each cheek and one on her forehead. This pattern was remarkably similar to those made on the faces of young women in the Punu or Tikar regions of Gabon around the time they started puberty. The diamonds on Nell’s face therefore suggest that she was likely old enough, when taken from Africa, to carry with her the knowledge of other regional traditions.

Enslaved people in densely populated areas like New York often sought out others who came from the same geographic region. In 1753, an advertisement for a self-emancipating enslaved man named Lewis Francois was printed in the New York Weekly Post-Boy. Francois had recently come from Jamaica, and the ad states that he “is supposed to be harboured by West-India Negroes of his Acquaintance.” This suggests that New York City was home to an active community of Caribbean people, perhaps both free and enslaved, who aided fugitives in their attempt to escape bondage.

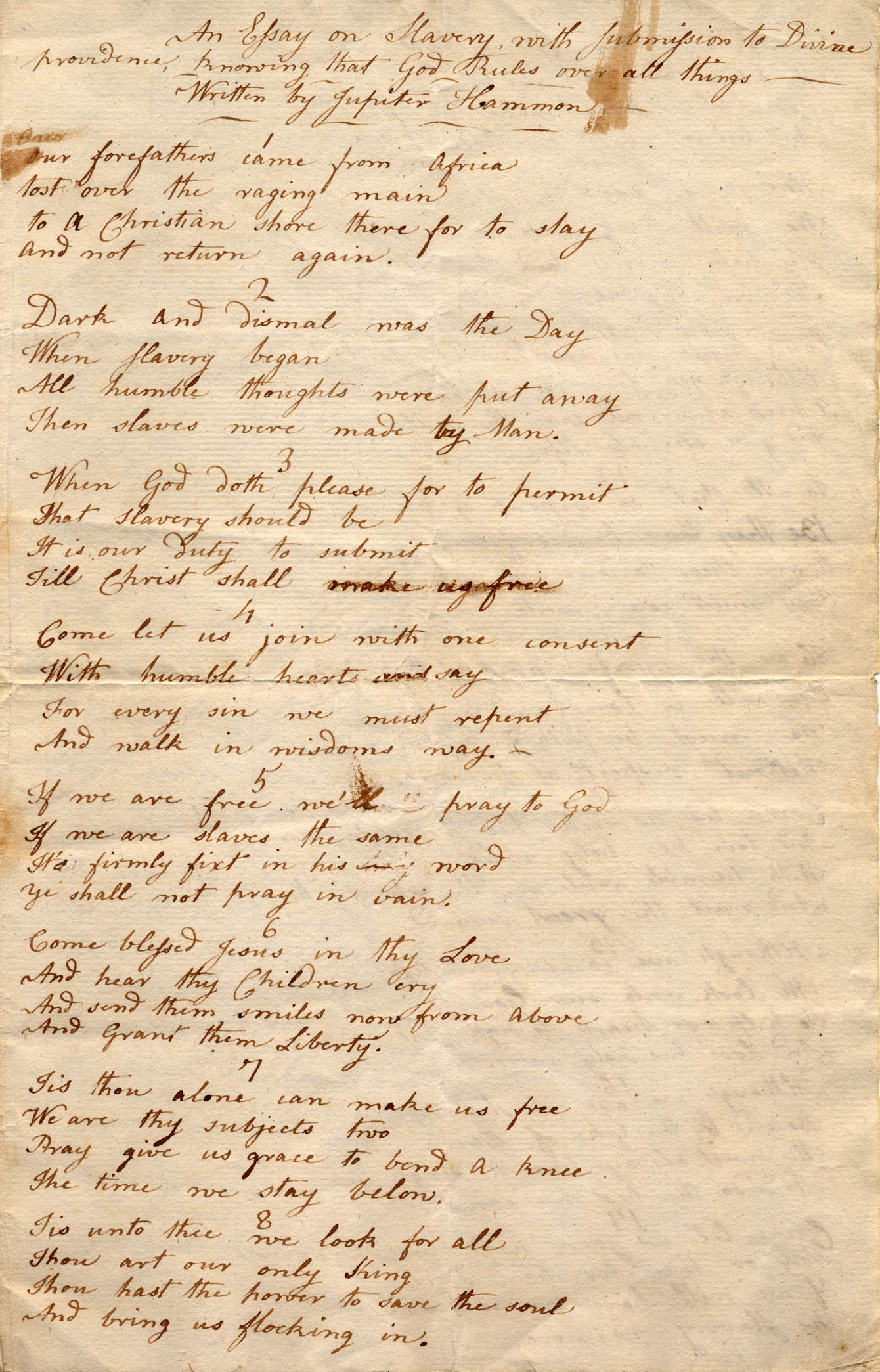

Storytelling was another way enslaved people could maintain a sense of community in the face of isolating circumstances. While African folktales left few traces in the written record, several enslaved people in the colonial North were celebrated for their published writing. They included Phillis Wheatley, Jupiter Hammon, and Lucy Terry Prince.

African-born poet Phillis Wheatley had received a classical education by her enslavers. Within a few years of her first published works, Wheatley was corresponding with influential ministers, English aristocracy, and future Presidents. In many of her letters and poems, she used the tools of her oppressors to push back against the institution of enslavement.

Jupiter Hammon was enslaved in Oyster Bay, New York, where he labored for the Lloyd family. Hammon adopted a devotional Christian style for his published poetry and sermons. Lucy Terry Prince was African-born and enslaved in Deerfield, Massachusetts. Prince composed and publicly recited her poem “Bars Fight,” memorializing the 1746 killing of white colonists by Native American warriors. Prince’s poem makes no reference to African culture, but instead takes up a theme more appealing to her captors. She was eventually freed and moved to Vermont, where she continued to perform “Bars Fight” in the style of a griot, or storyteller, until her death in 1821.

Enslaved people also maintained their culture through personal practices and observances. Gravesites in the African Burial Ground of lower Manhattan reveal some of the discreet ways that enslaved people preserved their cultural traditions, including evidence of teeth filing consistent with Congolese or Ghanaian culture, as well as “waist beads” which were worn by women along the Atlantic coast of Africa. Additionally, the bodies discovered at the burial ground were interred in traditional African arrangement, with the heads toward the west. This allowed for people in the afterlife to rise facing east.