The Philipse Family and the Slave Trade

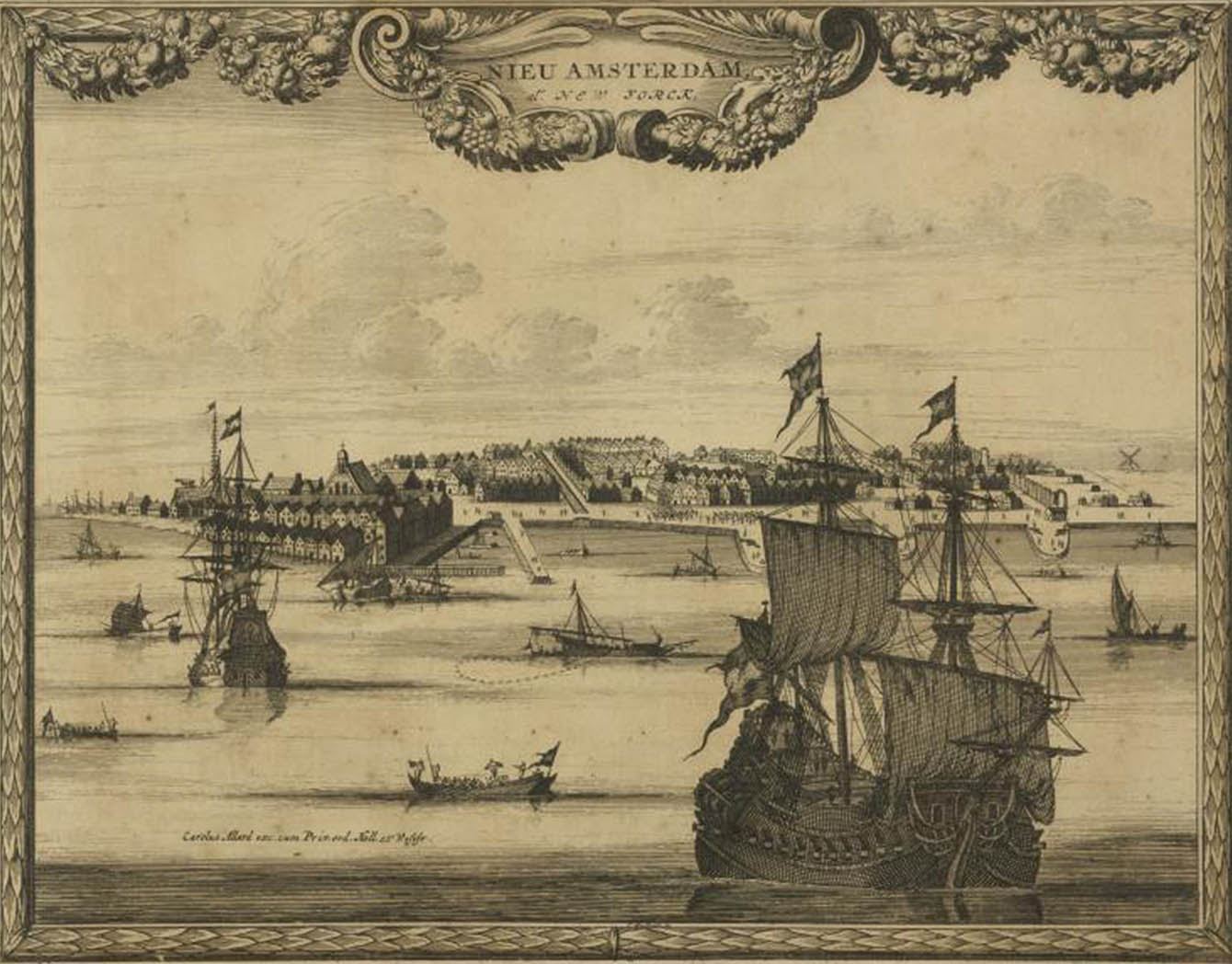

The Philipses were among the largest enslavers in colonial New York. Frederick Philipse (1626–1702) and his son, Adolph (1664–1750), owned a fleet of cargo vessels that sailed regularly to Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa. As early as 1680, their cargo included African captives. In addition to enslaving dozens of men, women, and children on their properties in Westchester County and Manhattan, they shipped thousands more enslaved people to sugar plantations throughout the Caribbean.

During the 1690s, the Philipses began trading African captives with pirates along the coast of Madagascar. This illicit trade yielded tremendous profit for merchants like the Philipses.

Because the island of Madagascar was outside the region of West Africa controlled by Britain’s Royal African Company, Frederick Philipse was able to send several associates there. They established a trading fort to circumvent the Royal African Company’s slave trade monopoly on Africa’s Atlantic coast.

One of the men sent by Philipse was a pirate named Adam Baldridge, who served as a broker between other pirates and potential enslavers. It was Baldridge, living on Madagascar, who enabled Philipse to purchase African captives there for a lower price than that of captives on the west coast. The potential profits outweighed the risks of the longer voyage. Between 1693 and 1699, Philipse-owned ships made at least five voyages to Madagascar for the purchase of more than 1,100 African captives.

Philipse hired a former pirate captain named Samuel Burgess to lead his slave-trading voyages between New York and Madagascar. In The History of the Pyrates, author Daniel Defoe noted that after two voyages Burgess had made a profit of 15,000 British pounds for Philipse,“ [and] 300 Slaves he brought to New York.”

In 1699, New York’s British Royal Governor, Lord Bellomont, wrote to the London Board of Trade, boasting about the expected enormous profits arriving on ships trading with pirates. Word spread and wealthy northern merchants and politicians soon started capitalizing on trade to Madagascar.

Within a year of Bellomont’s letter, orders from London led to the arrests of the pirates associated with the Madagascar trade, most notably Captain William Kidd.

The Philipses were sharply rebuked, not for their role in the slave trade, but for trading with known pirates. By 1701, New York’s trade with Madagascar had ceased, but the closure of the Royal African Company’s monopoly enabled merchants like the Philipses to continue their brutal transatlantic trade on Africa’s Atlantic coast. Records show that between 1720 and 1725, 809 African captives were forcibly removed to Barbados on Philipse’s fleet.