More Stories About Family

The bonds of marriage did not protect enslaved men and women from forced separations, nor did an impending birth or any other family connection. Even when enslavers recognized family relationships, they often chose to ignore them. Nevertheless, the following entries, taken from inventories, bills of sale, runaway advertisements, birth registries, and cemetery ledgers, bear witness to the enduring human impulse to create families, even in the face of likely separation, and hold fast to them through any adversity.

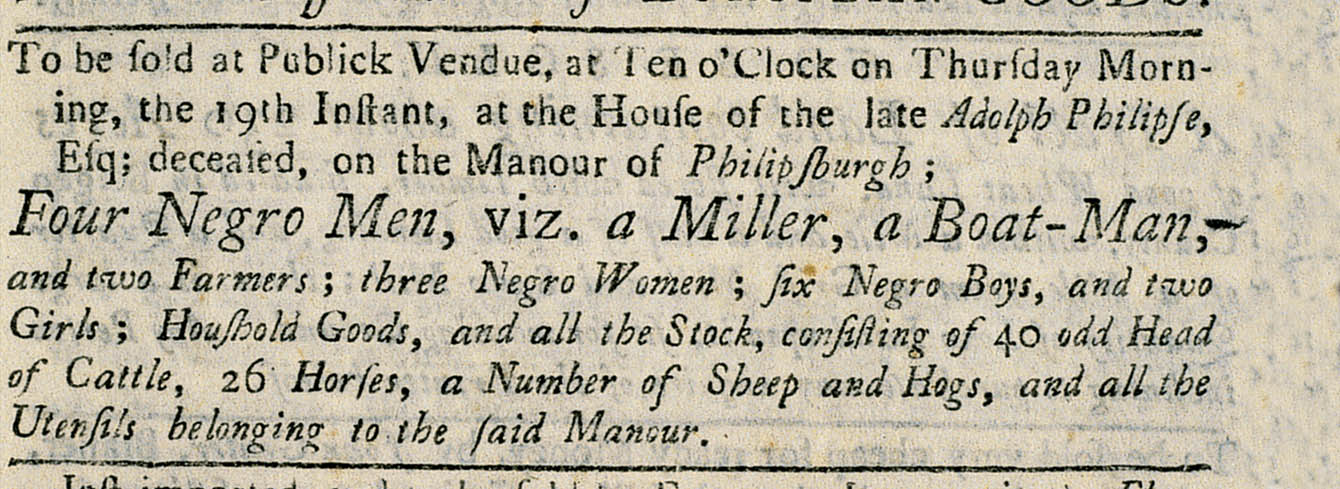

Although no evidence exists proving kinship among the enslaved residents of Philipsburg Manor, a pattern of shared first names among the men and boys suggests father-son relationships. In 1750, an auction was held at Philipsburg. Fifteen enslaved individuals, livestock, and "household utensils" were put up for bid. An eight-year-old child named Sam was sold that day, alone. Sampson, his likely father, had been sold a month earlier. Sam’s mother was probably one of the enslaved women at Philipsburg, and she may have witnessed her child’s auction. The community built by the enslaved residents of Philipsburg Manor was surely torn apart by their enslavers that day.

Children born to enslaved mothers became the property of their enslavers, thereby creating a new generation of labor. The Greenwich, Connecticut Commonplace Book notes the births of Cull (1801) and Jack (1802), the sons of Patience and Candice, who were enslaved by the Bush family. The 1820 Federal census for Greenwich shows all four listed as “slaves,” indicating that they had remained together.

In some cases, even very young children were sold away from their mothers. In 1721, Sampson, a 19-month-old baby enslaved by Nathaniel Church of Little Compton, Rhode Island, was sold to Church’s cousin, William Shaw, for £38.

Enslaved women were sometimes sold simply because they were pregnant. For an enslaver, pregnancy could be seen as an impediment to work, and an infant as a distraction. A 1781 Connecticut advertisement is explicit about the reason for the sale of an enslaved woman: “TO BE SOLD, An extraordinary likely Negro Wench, 17 years old, she can be warranted to be strong, healthy, and good natur’d, has no notion of Freedom, has been always used to a Farmer’s kitchen and dairy, and is not known to have any failing, but being with Child, which is the only cause of her being sold:...”

Children were also mentioned for sale without a parent. The Logan's noted the purchase of a boy, Jack, and a girl, Arimina, at Stenton, outside Philadelphia. No records exist regarding their family circumstances: only their value as a commodity was important in this transaction between enslavers.

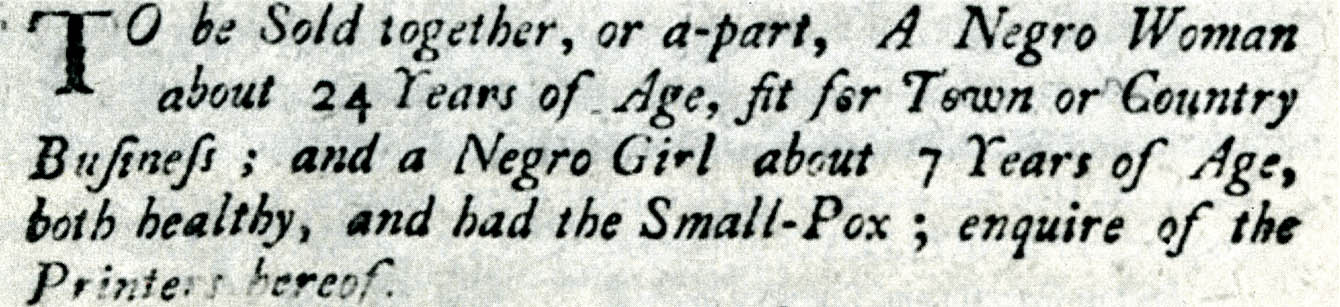

Numerous documents list enslaved children while ignoring family connections. A Boston newspaper advertised “A Negro Woman, about twenty-four Years of Age… and a Negro Girl, about seven Years of Age,” “to be sold Together or a-part [sic].” That these individuals are listed together suggests that they are mother and daughter, but this relationship was not important to the seller.

A chilling reminder that colonial law recognized the protection of personal property over the bonds between mother and child is evident in a 1778 New Jersey advertisement. The enslaver offered a $200 reward for a “nine or ten”-year-old girl named Dianah who “[w]as stolen by her mother,” an enslaved woman named Cash. The language of this advertisement clearly shows that colonial law did not recognize the rights of enslaved parents. Cash’s effort to reunite with her daughter was considered an act of theft.

By contrast, Pierre Van Cortlandt’s 1814 manumittance noted one enslaved family who remained together in bondage and in freedom: “Ishmael a Neagro [sic] Man and Sibby his wife and Abbey their daughter[,]...” Ishmael worked as a coachman for the Van Cortlandts. He also earned money playing the fiddle at parties in the homes of the Van Cortlandts’ neighbors. Sib likely cooked and provided household support. An 1804 bill to Pierre Van Cortlandt from Jacob Lent for “schooling for Black Abbey” suggests that Abbey received some education. It was most likely that this “schooling” was vocational, designed to help Abbey with her household tasks.

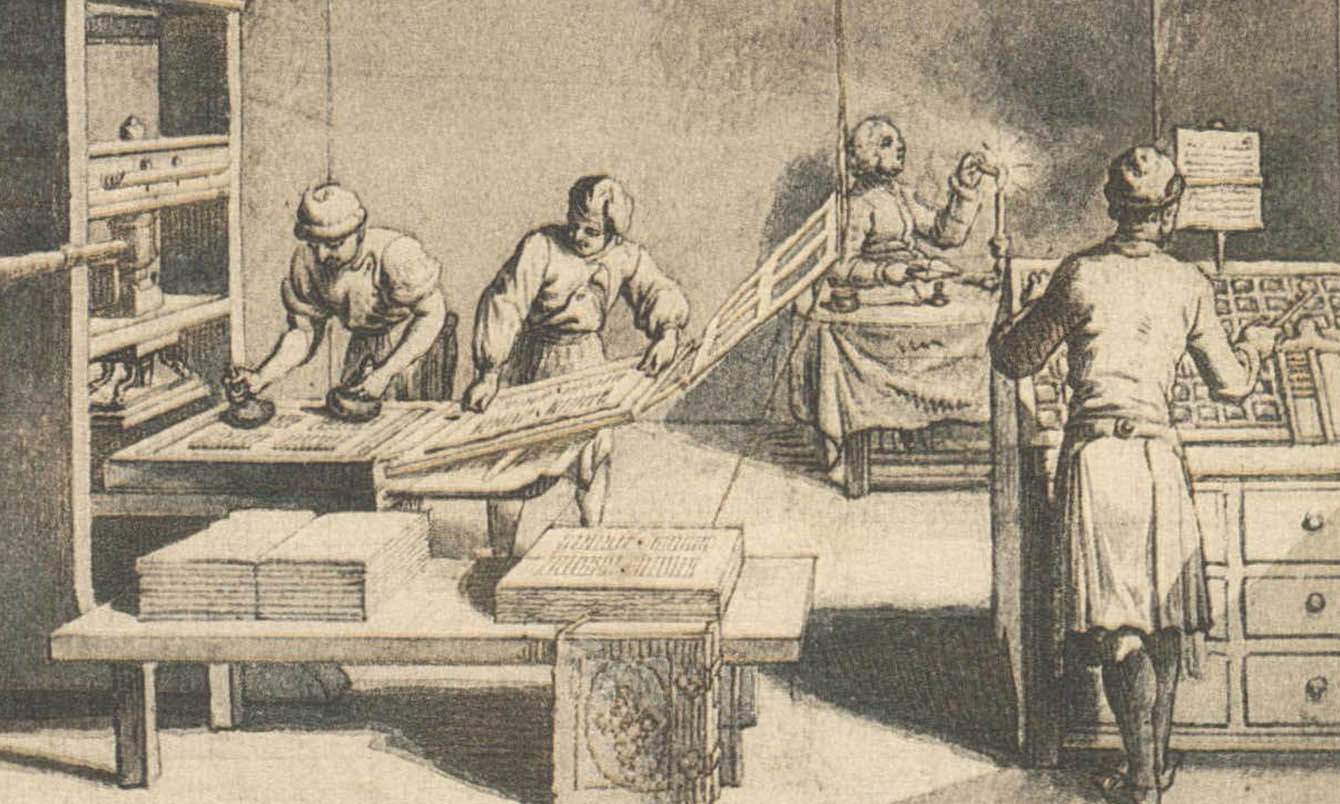

Because enslaved labor was by definition unpaid, it was rare for an enslaved person to be able to save money, and rarer still to be able to bequeathed it to family. Peter Fleet, an enslaved woodcut maker in a print shop in Boston, had this chance. He drew up a will and bequeathed money that he had received from customers to his children. He also left a lesser amount to his enslaver’s children. This might have been a strategic decision, designed to generate goodwill with his enslaver and protect his children’s inheritance after his death.

Even in death, enslaved children were still considered property by their enslavers. The records of the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia list the interment of an unnamed “Negroe child slave to the widow Thompson” on March 2, 1745. Christ Church Burial Ground is the graveyard of many prominent white Philadelphians, including Benjamin Franklin, but also of enslavers and some of the enslaved individuals who worked for them. Unlike Franklin, who was buried next to his wife and children, this child appears to have been buried alone with no permanent marker—no one even recorded a name or gender in the church registry.