Stories About Using the Law

Colonial law made it all but impossible for enslaved people to appeal to the courts for freedom from bondage. In fact, nearly 130 years passed between the first and second times the law was successfully challenged.

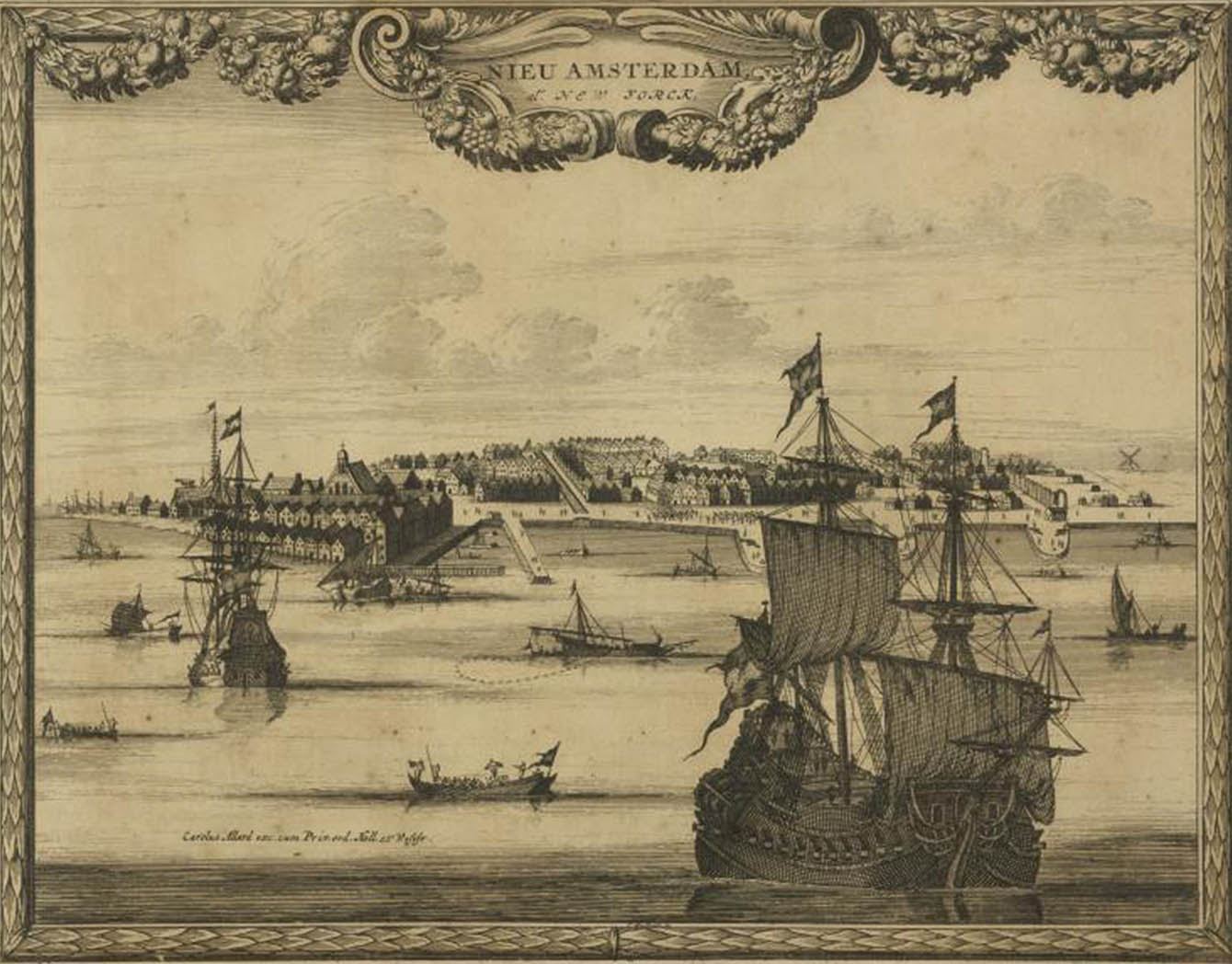

When 11 African captives were delivered to the Dutch colonial outpost of New Amsterdam in 1626, slavery had not been clearly defined. Because of this, some Africans were able to use the law to secure partial freedoms. In 1644, a group of permanently indentured Africans sued for their freedom. The Dutch West India Company, the overseers of New Amsterdam, granted freedom to these men and their wives, but their children, both those “already in existence [and those] hereafter born, shall be slaves.”

In an effort to remain near their enslaved children, the freed men and women did not leave the area.

Town leaders also wanted the freed men close by and granted them farmland outside the town’s defenses in what is now Greenwich Village. Known as the “land of the blacks,” the area became a buffer zone between New Amsterdam, hostile indigenous populations, and potential English invaders from Connecticut.

As a result of this lawsuit, a few free black communities developed in the greater New York area and survived for more than two centuries. After the British seized control of New Netherland, highly restrictive laws defining slavery were instituted, making legal actions like this impossible until the time of the American Revolution.

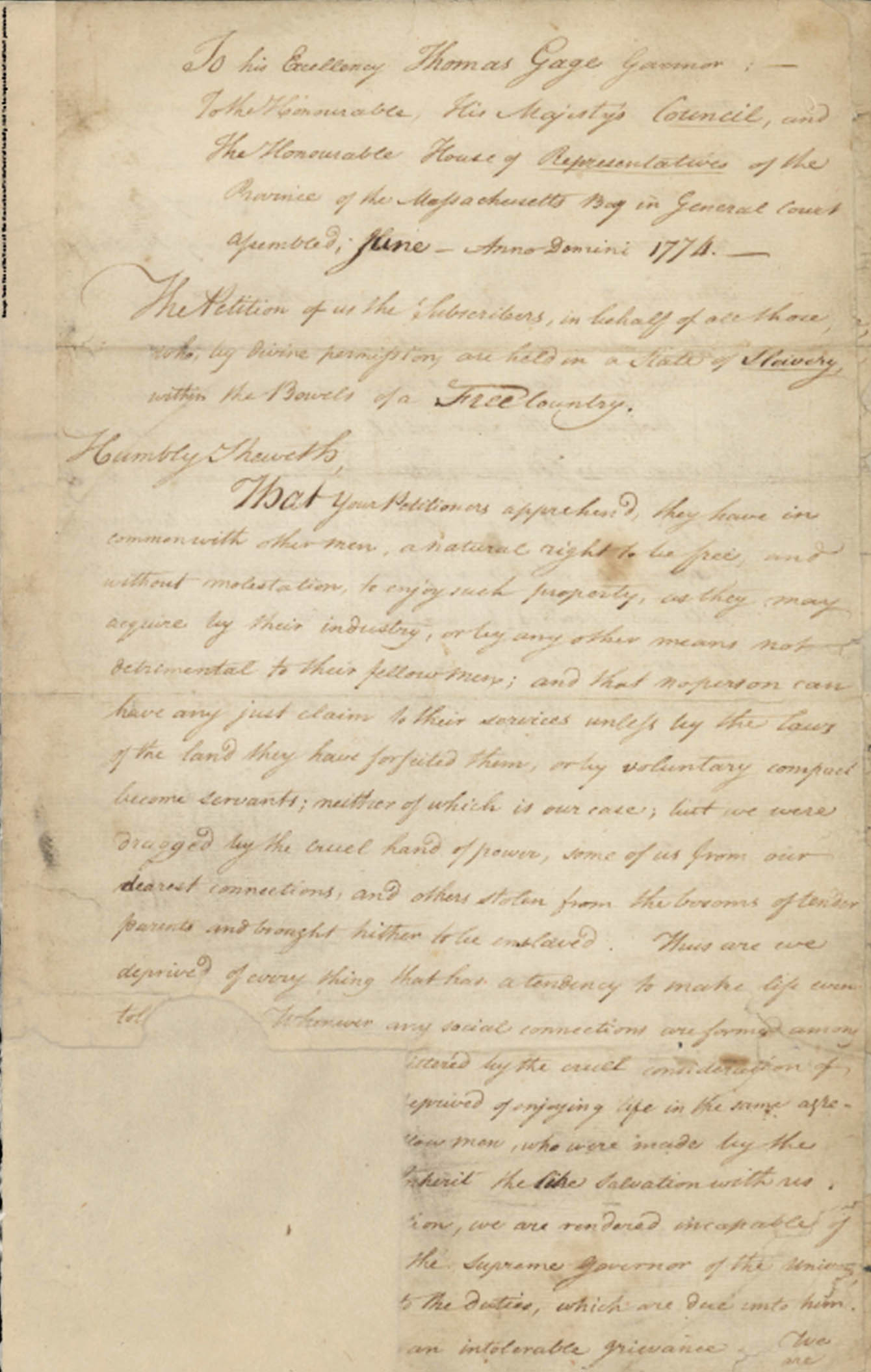

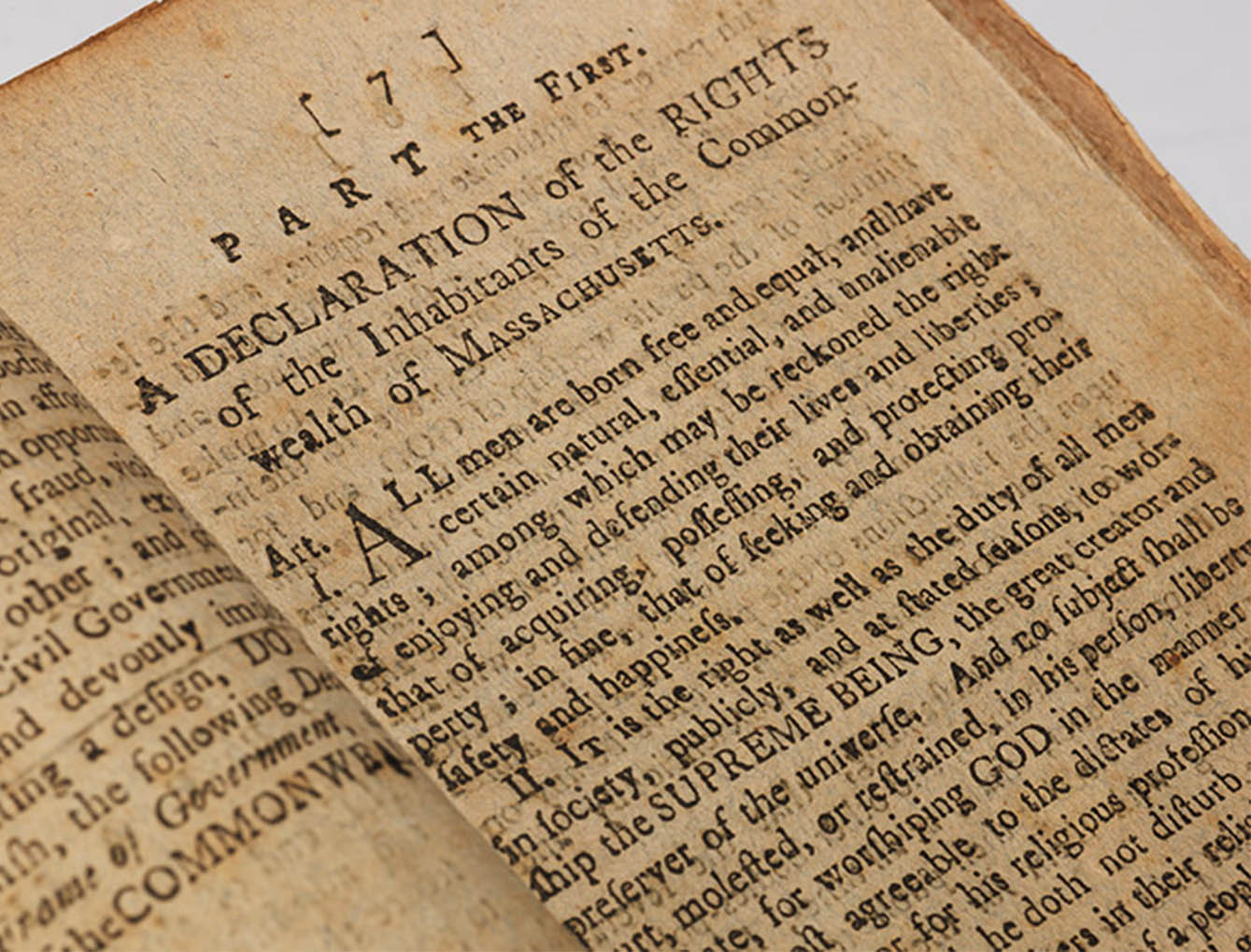

Freedom suits filed after the creation of Massachusetts’ new State Constitution were more successful. Article I of the constitution stated that “All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights.” Some enslaved individuals capitalized on this statement and took action to end enslavement in the Commonwealth.

Elizabeth Freeman (known as Bett at the time) was enslaved by John Ashley of Sheffield, MA. Ashley was active in Revolutionary politics, and his home often served as a center for local meetings. In January, 1773, the Sheffield Resolves, a precursor to the Declaration of Independence, was ratified there.

In 1780, Massachusetts’ new constitution was read at Ashley’s house. Bett listened to her enslaver as he spoke in favor of freedom and independence. A year later, she and Brom, an enslaved man in Ashley’s household, met with Theodore Sedgwick, author of the Sheffield Resolves. With Sedwick’s help they sued Ashley for their freedom, arguing that the new State constitution disallowed slavery. The jury ruled against Ashley, and Bett and Brom were freed.

Brom and Bett v. Ashley set a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. The Quock Walker cases that followed built on that success, rendering slavery unconstitutional in Massachusetts.

Walker was enslaved by James Caldwell of Worcester, who promised to free him when Walker reached adulthood. Caldwell died when Walker was ten, but Caldwell’s widow, Isabel, said she would honor that promise of freedom. When Isabel died, her second husband, Nathaniel Jennison, refused to free Walker at all. At the age of 28, Walker chose to self-emancipate, returning to James Caldwell’s family, whom he may have trusted.

Jennison captured Walker and beat him. He then sued the Caldwells for encouraging Walker to flee, while the Caldwells asserted that Walker should have been freed as promised.

A series of suits and countersuits followed. Jennison appealed his case to the Supreme Court of Massachusetts, arguing that Walker was a fugitive from slavery. Walker’s attorneys argued that the creation of the Massachusetts Constitution in 1780 had made enslavement illegal. Chief Justice William Cushing ultimately accepted Walker’s argument, thereby setting a precedent that gradually ended slavery in Massachusetts.

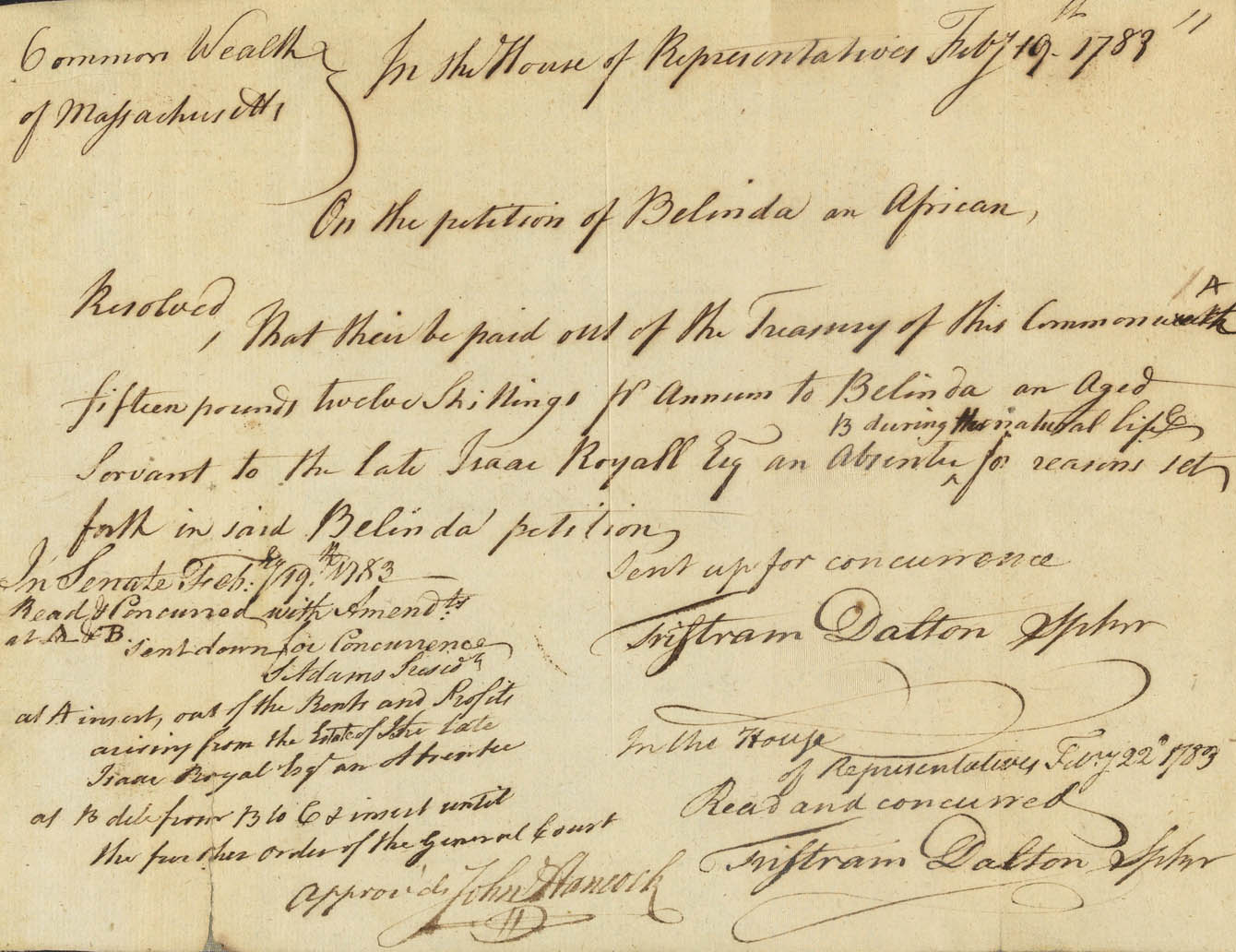

The Freeman and Walker lawsuits determined that slavery could not continue in Massachusetts under its new constitution. One woman petitioned the courts to compensate for her years of enslaved labor. Belinda Sutton was an African-born woman enslaved for 50 years by the wealthy merchant Isaac Royall, Jr., of Medford, MA. In 1783, Sutton, now free, petitioned the General Court for a pension for her enslavement. Her appeal was the first to ask for reparations for a lifetime of forced labor. Sutton was awarded an annual pension by the court, but the Royall family delayed payments and Sutton received only a fraction of her award.

Freedom suits were rare outside of Massachusetts. In 1787, the newly adopted US Constitution, while never mentioning the words “slave” or “slavery,” actively protected the rights of enslavers.

Article I, Section 2 of the US Constitution declared that enslaved persons in each state would be counted in the Federal census. To determine Congressional representation, each enslaved person was counted as 3/5 of a person. By allowing 60% of an enslaver’s human property to be included for political representation, the Constitution made possible the overrepresentation of southern states where enslaved populations continued to grow.

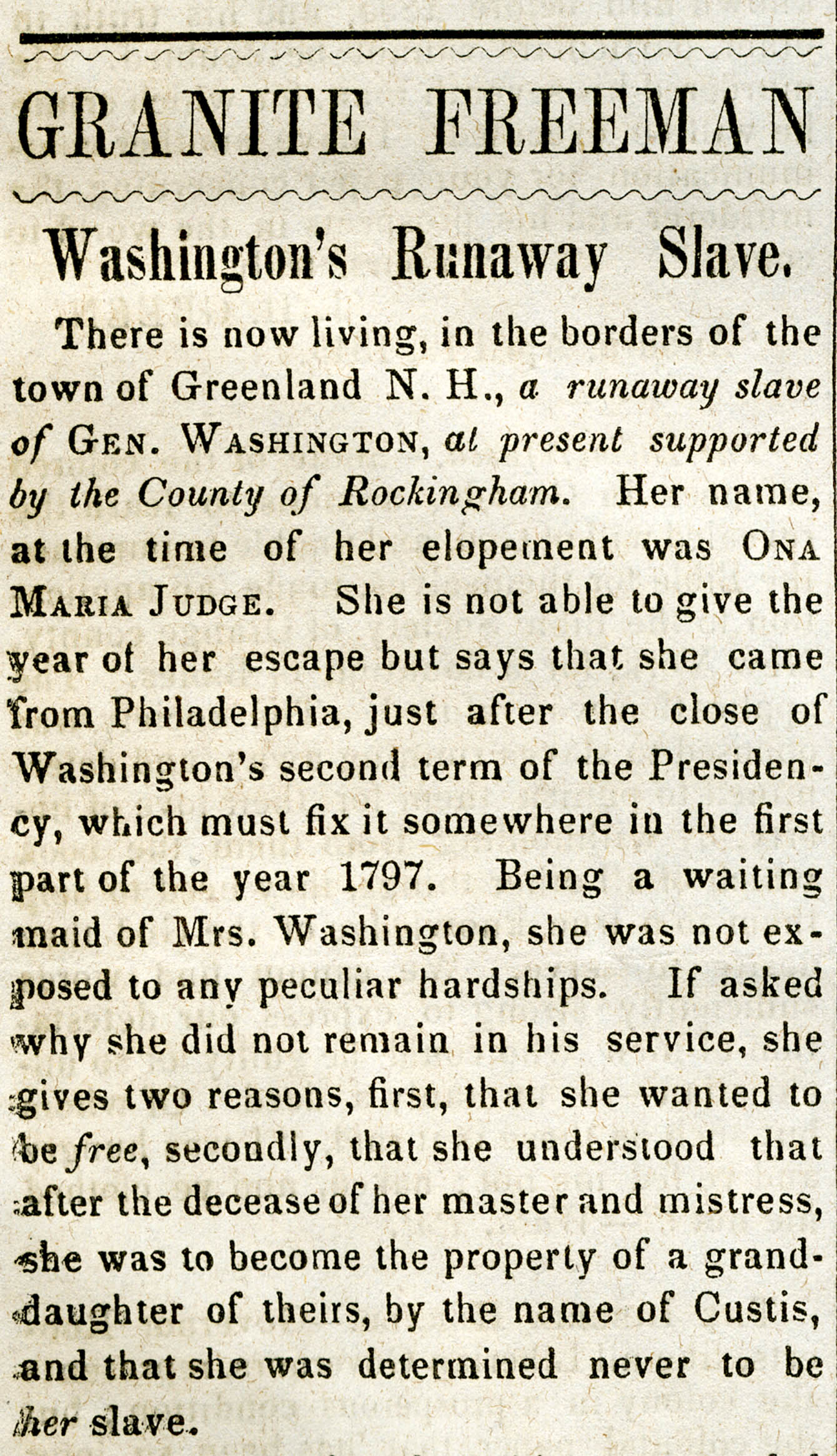

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 provided the legal mechanism to enforce the constitutional clause requiring each state to return fugitive slaves and servants to their lawful claimants. Perhaps the best known of the colonial enslavers who used this law was General George Washington, the first president of the United States.

Ona Judge was one of 153 “dower slaves,” or enslaved individuals inherited by an enslaver, who were held by Washington’s wife, Martha. Judge served as a personal maid to Mrs. Washington and was brought to New York City, and then Philadelphia, during George Washington’s presidency.

In 1796, Ona Judge self-emancipated with the help of Philadelphia’s free black population, and made her way to New Hampshire. President Washington invoked the Fugitive Slave Act and sent several federal agents to New Hampshire to seize her. Each time, Ona Judge avoided capture. Late in her life, a reporter asked Judge if she regretted her escape. She replied, "No, I am free, and have… been made a child of God by the means.” According to the laws of the United States, however, Ona Judge was never officially freed. She died a fugitive in 1848.