Stories About Elders

Enslavers valued the people they held in bondage by the work they could do: the more they were capable of, the more they were worth. Elders were not considered to be productive workers, and were worth little to their enslavers. The true value of these elders only becomes evident through reading between the lines of official documents.

Inventories provide a stark example of how the worth of human beings was calculated by their enslavers. At Lloyd Manor on Long Island, the circumstance of age is made clear in a description from John Lloyd II’s 1793 surviving inventory: “Three old Negroes, Viz.—John Potter & His Wife Judith, and old Hannah, which being nearly past labor, we think as of no value…” Lloyd’s cold statement ignores Hannah’s accumulated experience and likely contributions to the enslaved community. Being “nearly past labor,” she ceases to have value for her enslaver.

A 1797 property inventory for Lucan Von Beverhoudt in Morris County, New Jersey, lists four enslaved men—Noe, Lewe, Mahoe, and Mingo, aged 75, 70, 60, and 50 respectively—as having zero monetary value. Another 50-year-old man, Muchoe, was listed at just over seven pounds. Enslavers often attempted to sell men and women prior to age 50, before the costs of feeding and clothing them outweighed their capacity to be productive for their enslavers. Although no longer considered profitable by Von Beverhoudt, these individuals were likely considered valuable members of the enslaved community, which would have cared for them as part of their shared responsibilities.

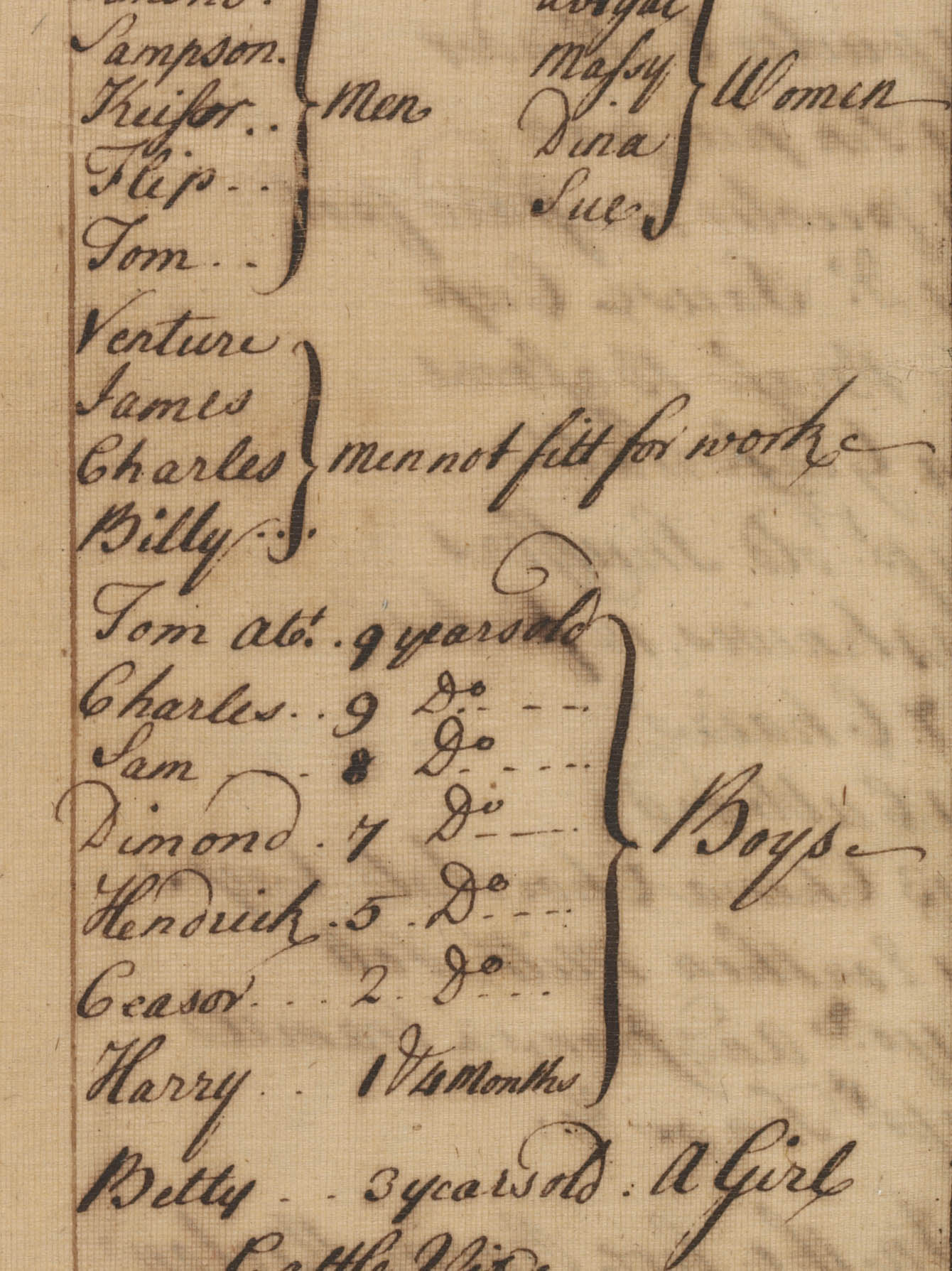

The Philipsburg Manor inventory of 1750 lists four men—Venture, James, Charles, and Billy—as “not fit for work.” Two of these men, Charles and Billy, had been among 16 enslaved people inherited by Adolph Philipse 48 years earlier, and would have been considered elders by 1750. Together, Charles and Billy would have possessed a deep knowledge of Philipse’s Upper Mills plantation that would have benefited their community in many ways. In addition to professional expertise, they might have shared the accumulated wisdom of 48 years at Philipsburg Manor, and taught other enslaved people the strategies necessary to survive.

Even when northern states began to adopt emancipation laws, elders were often excluded because of their advanced age. When Pierre Van Cortlandt manumitted the enslaved people in his household in his 1814 will, including Ishmael, Sib, and Abby, a woman named Phillis was not freed. At the age of 48, she was older than the legal age allowed for manumission in New York. Restrictions upon freeing elderly enslaved men and women were meant to ensure that private citizens, not the state government, remained responsible for their care. This practice, however, rarely took the wishes of the enslaved elders into account.

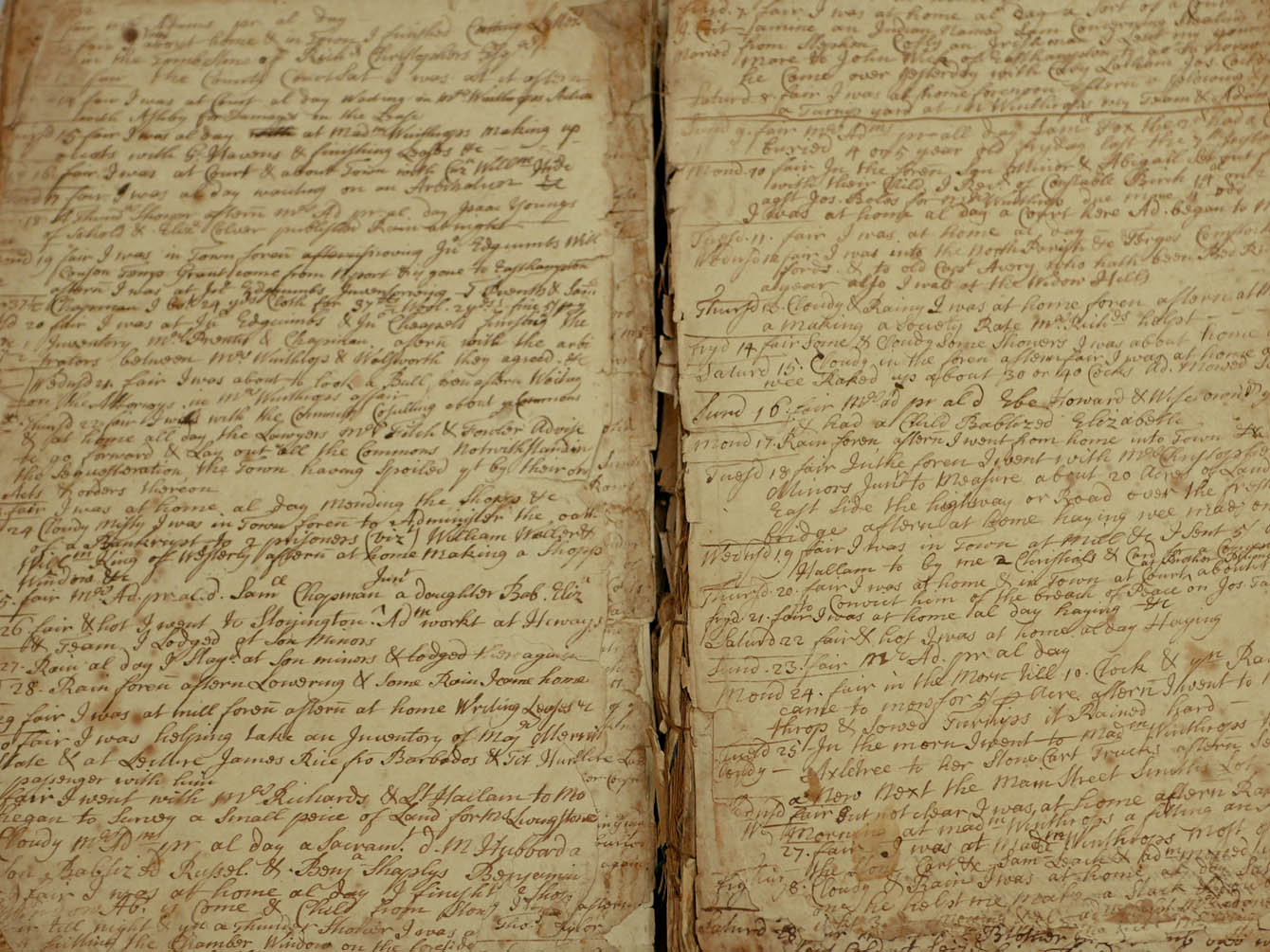

Born in New London, Connecticut, around 1702, Adam Jackson was the eldest son of Joan and John Jackson. Although Adam’s father was a free man, his mother was enslaved when she gave birth to Adam, which meant that Adam was enslaved by law. For more than thirty years, Adam Jackson was the only person enslaved by local shipwright and justice Joshua Hempsted. When Adam was in his late fifties, Hempsted died.

Shortly after his enslaver’s death, Adam Jackson was freed by the Hempsted family. What could freedom have meant for Adam Jackson? He was nearly 60, an age that was considered elderly in colonial America. The few surviving documents and New London records note that Adam Jackson remained at the lowest level of the New England tax rolls for the four years that he lived as a freedman. Although the Hempsted family granted Adam Jackson his freedom, it was, at Jackson’s advanced age, simply the freedom to be poor.

Reverend Stephen Williams of Longmeadow, MA, recorded the death of an older enslaved woman in his household, also named Phillis. On May 28, 1774, he wrote: "this [morning] dy'd… my Negro woman;... phillis had ye charactr of being Honest--& I hope had had Sight of [Christ] by faith." The following day he noted the circumstances of her funeral: "aftr meeting at night-- phillis was buri'd -- considerable number of people attend'd ye funeral--" Phillis’s importance in her community is signaled by Reverend Williams’ comment about the “considerable” attendance at her funeral. A nighttime funeral was likely necessary because enslaved mourners and family were required to work during the day.

Clues about how elders in New York’s enslaved community retained elements of their West African culture came to light with the rediscovery of the African Burial Ground. Forensic evidence identified “Burial 340” as a 39-to-64-year-old woman with strong ties to Africa. While her name is lost to history, it is known that the woman’s teeth had been filed in a practice known to mark life events for Congolese or Ghanaians. Her remains also included decorative beads, possibly waist beads, from West Africa. These physical clues suggest this woman may have also retained other intangible cultural connections to traditions that she shared with other enslaved people.

Because they were so often overlooked by their enslavers, documents attesting to the specific roles of enslaved elders are rare. However, it was typical for elders to train or supervise younger children in enslaved communities. They would have also shared various African and West Indian traditions, enabling the creation of a common heritage. Food, music, storytelling, and poetry are among the ways that elders could pass on valuable life lessons. This in turn contributed to the development of a uniquely American culture.

Twentieth-century Sengalese poet Birago Diop's (1906–1989) poem, “Forefathers,” speaks to the enduring presence of enslaved elders in the memories of their descendants.