Stories About Gradual Emancipation

Because gradual emancipation had been devised for the benefit of northern enslavers, its implementation was cruelly slow. The complicated state laws enacting gradual emancipation created conditions where children served decades-long “indentureships” while their parents and older siblings remained enslaved for life. It was also common for enslavers to sell enslaved individuals to southern states where slavery remained legal—sometimes in defiance of their own state laws—thus denying them any chance at freedom. For many enslaved individuals, the years spent living through gradual emancipation were filled with uncertainty.

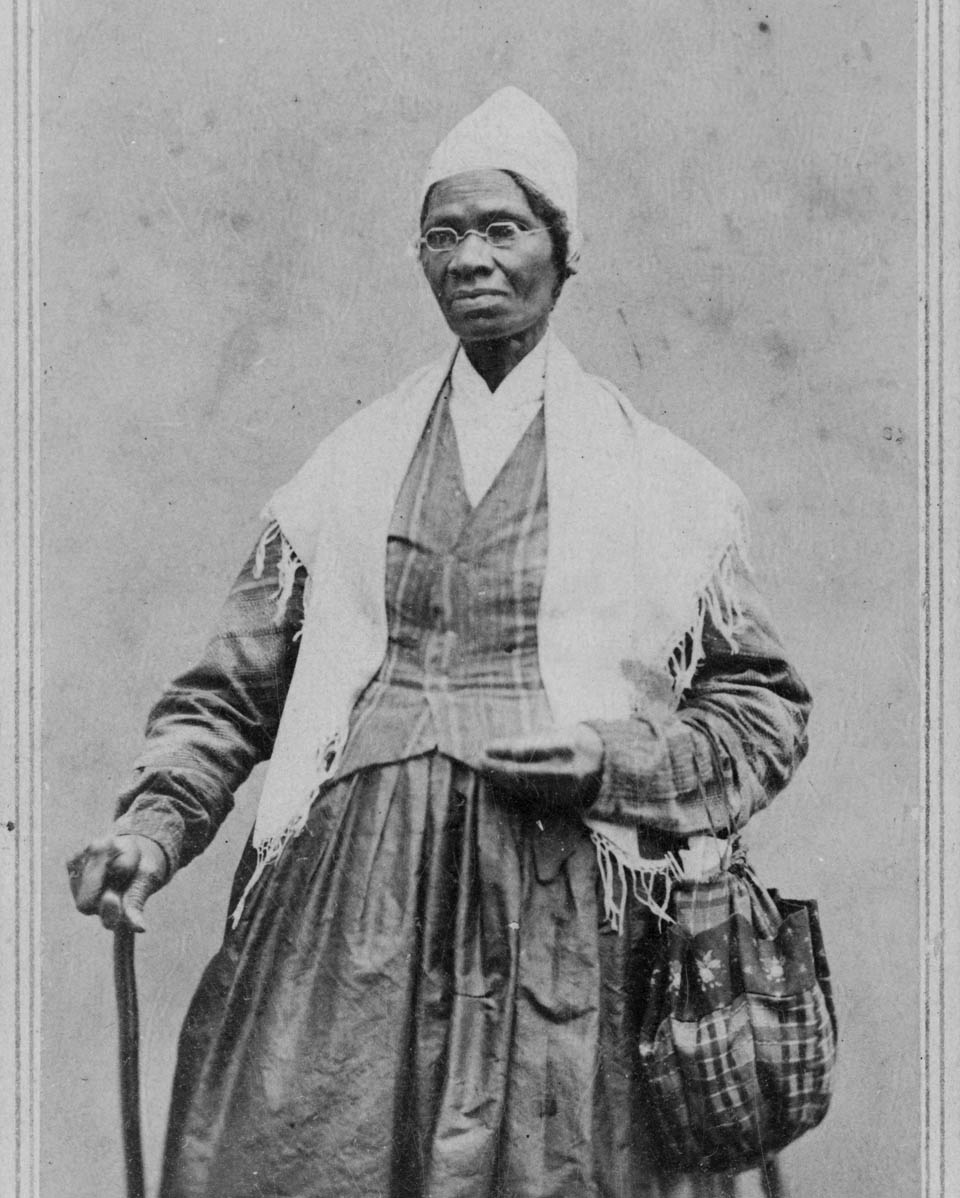

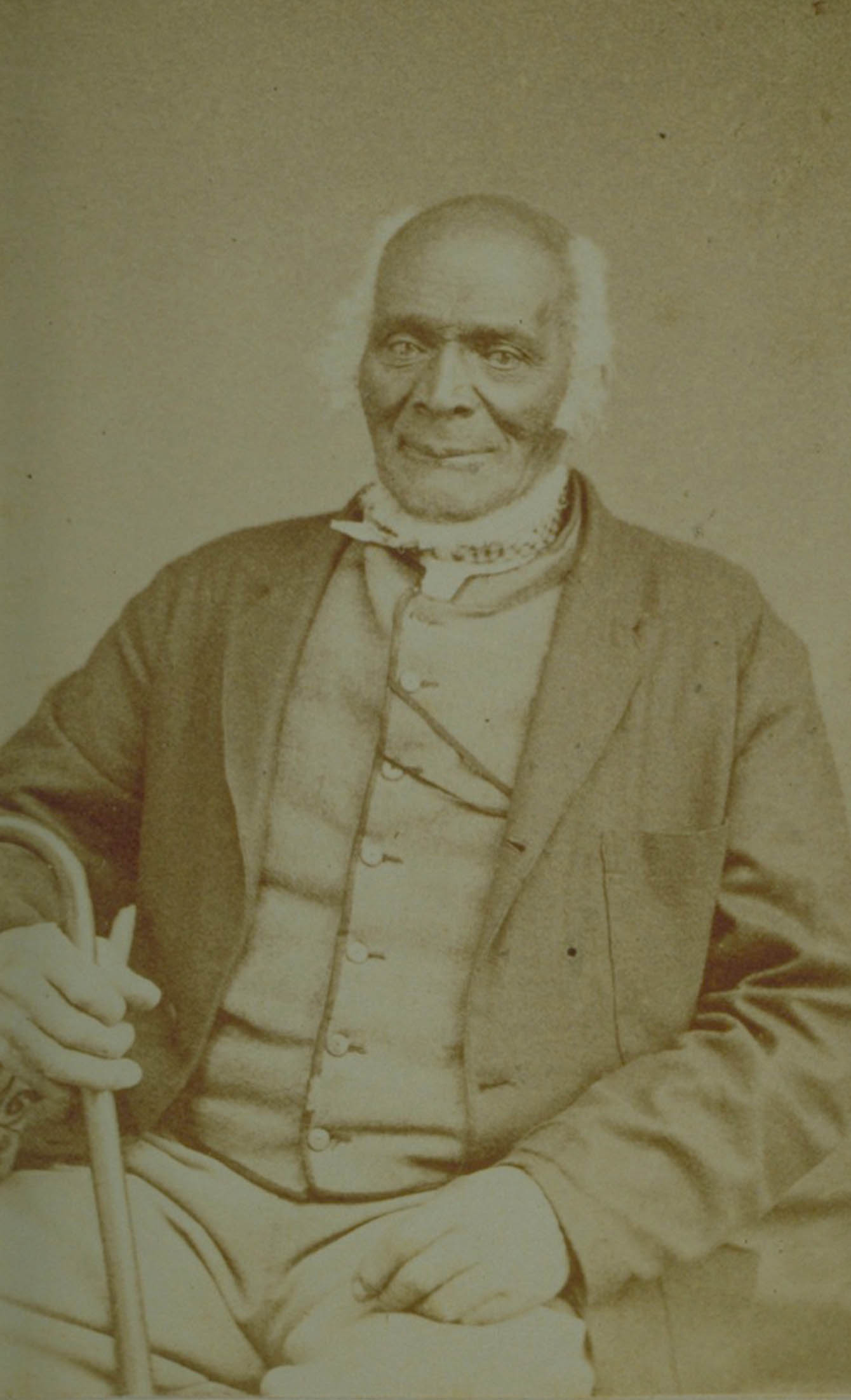

Many enslaved individuals were concerned that their enslavers would sell them to southern planters. State laws prohibiting such acts were rarely enforced. Sojourner Truth (c. 1797–1883) was born Isabella Baumfree in Ulster County, NY. Baumfree would not take the name Sojourner Truth until 1843, long after she secured her freedom. At the age of nine, Baumfree was sold and separated from her family. She was sold three times in four years before being purchased by John Dumont. While enslaved by Dumont, Baumfree married and had five children.

New York’s gradual emancipation act would free nearly all enslaved people in New York on July 4, 1827. Baumfree learned that Dumont planned to sell her to a slaveholding state before emancipation. Baumfree chose to self-liberate, taking her infant daughter, Sophia, with her. She was aided by the Van Wagenen family who hid her and eventually purchased her freedom from Dumont.

One of Baumfree’s first acts as a free woman was to successfully sue for the return of her son, Peter, who was sold to a plantation owner in Alabama. Later, as Sojourner Truth, Baumfree became a pioneering female abolitionist and women’s rights activist.

James Mars also used self-emancipation to avoid enslavement after gradual emancipation. Mars was born in Connecticut in 1790. Enslaved to Amos Thompson, Mars expected freedom at age 25 under Connecticut’s gradual emancipation act. Thompson, however, wanted to move to Virginia and bring James and his brother with him. With help from local residents, the Mars brothers left Thompson and evaded their move south. This caused Thompson to sell each brother to separate enslavers in Connecticut. By 1815, both men had been freed.

In 1864, Mars wrote an autobiography because “[s]ome told me that they did not know that slavery was ever allowed in Connecticut.”

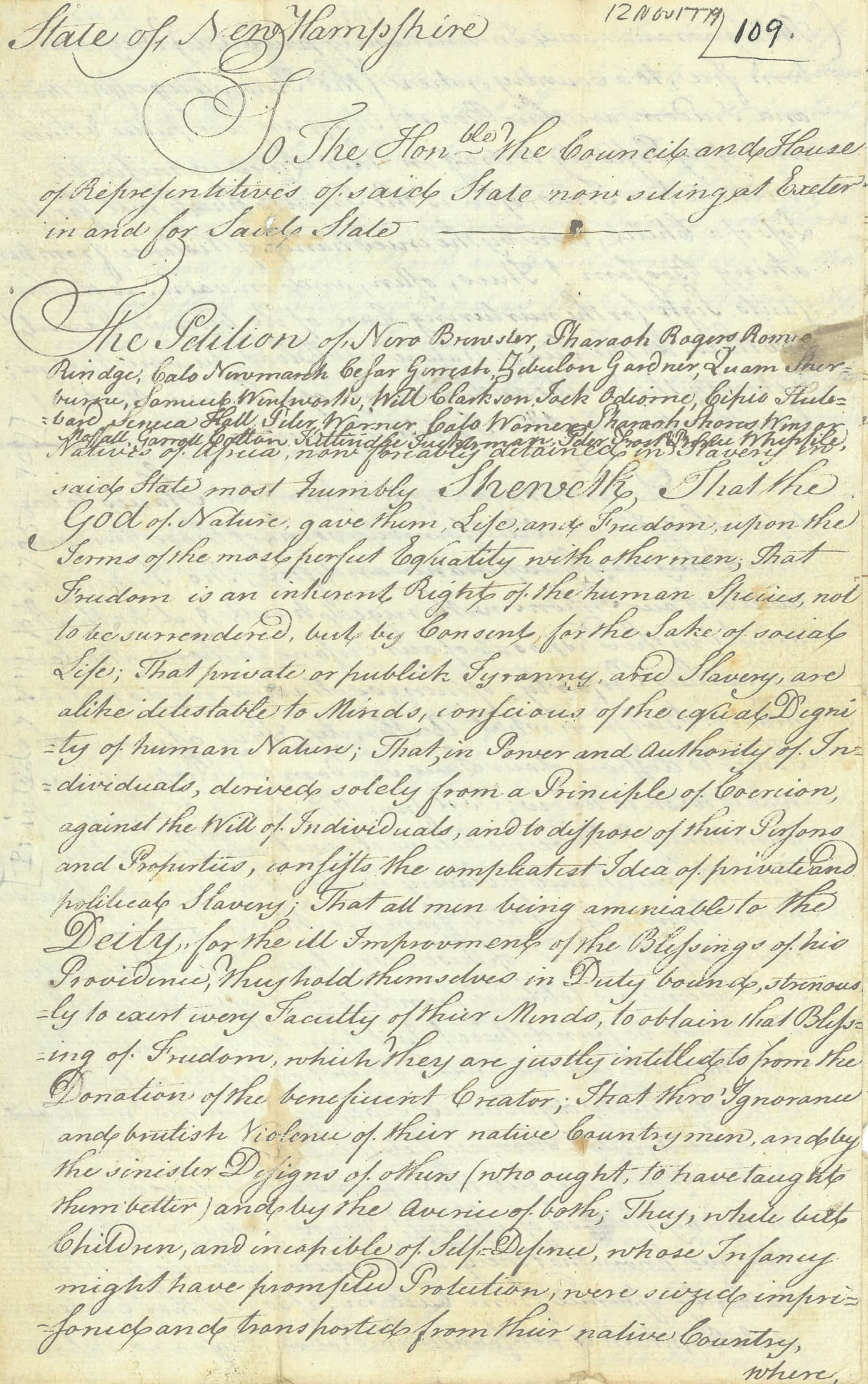

Like Massachusetts, New Hampshire never passed a gradual emancipation act because its state constitution was broadly interpreted to have banned enslavement. In 1779, 20 enslaved men from Portsmouth petitioned the state legislature for their freedom. The enslaved men stated that “freedom is an inherent right of the human species.” Their petition was rejected.

One of the petition's signers, Prince Whipple (1750–1796), had fought in several battles of the American Revolution. His enslaver, William Whipple, signed the Declaration of Independence. Although Prince Whipple did not receive freedom in 1779, he was able to secure his manumission in 1784, one year after New Hampshire’s constitution was adopted.

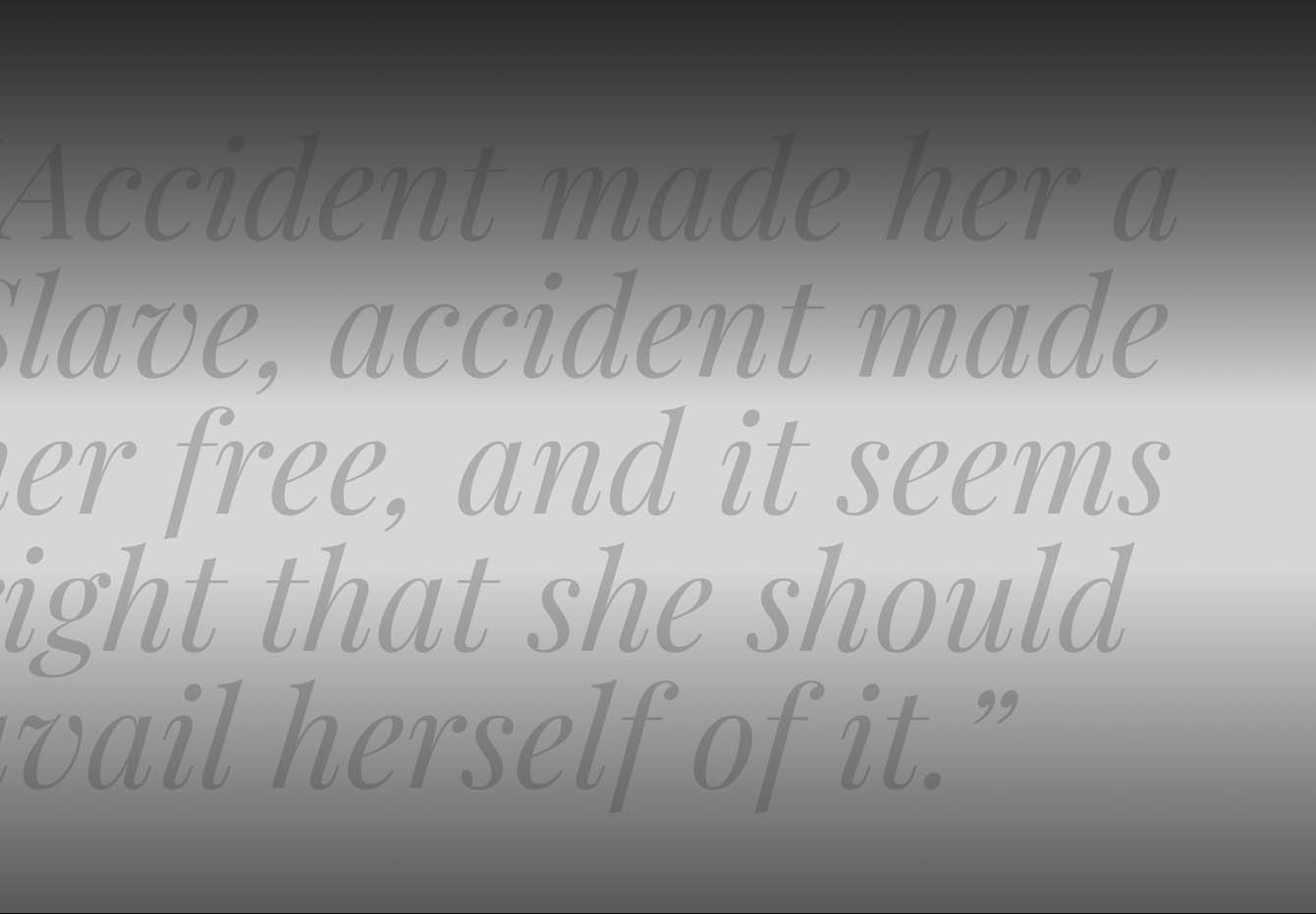

The story of Charity Castle shows how anti-slavery sentiment began to take hold in early 19th-century Philadelphia. In May, 1814, Charity Castle, an enslaved woman from Maryland, accompanied her enslaver, Harriet Chew Carroll, on a visit to the Chew family home in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania law stated that enslaved people entering the state would be freed after remaining there for more than six months. When Charity Castle heard that she was going to be sent back to Maryland, she told Carroll that she did not want to go because she had been abused by Carrolls husband.

Shortly before she was to leave Philadelphia, Charity Castle had an accident that left her injured and unable to be returned to Maryland. Due to the accident, Charity Castle spent more than six months in Pennsylvania, and by law she should have been freed. The Carrolls refused to free Castle, and claimed that because her accident caused the delay the law did not apply. Charity Castle’s husband, a free man living in Philadelphia, contacted an anti-slavery lawyer, William Lewis, to represent Castle in a legal challenge against her enslavement. Castle’s husband and William Lewis negotiated with the Carrolls to purchase Charity Castle’s freedom for $300.

Gradual emancipation gave northern enslavers more time to profit from forced labor and to enact legislation restricting the growing free black population from voting, owning property, and access to equal rights. As early as 1838, trains in Massachusetts had separate cars for black and white passengers.

Racist beliefs throughout the North meant that anti-slavery societies and abolitionists were not widely supported. The notion that most white northerners supported the underground railroad, aiding enslaved individuals who self-emancipated from slaveholding states, is untrue. The safe stops and houses that made up the underground railroad were more likely to be run by African Americans with a small number of trusted white individuals.