The Philipsburg Manor Inventory

Explore Adolph Philipse’s 1750 probate inventory. Discover what this primary document reveals about the enslaved community at Philipsburg Manor and learn what happened to them after the death of their enslaver.

Aerial view of Philipsburg Manor

Philipsburg Manor, Sleepy Hollow, New York.

Historic Hudson Valley.

The Manor (“the manour”)

This New York property was a 52,000 acre provisioning plantation more than triple the size of Manhattan, with a water-powered gristmill that was key to production and a profitable dairy operation. The community of enslaved people who lived here was torn apart after the death of Philipse, the plantation’s owner, in 1750.

Adolph Philipse

c. 1695

Unknown

Adolph Philipse, merchant and politician, the owner of Philipsburg Manor.

Artist unknown / Museum of the City of New York. 33.45.

Philipsburg (“Philipsburgh”)

The plantation's namesake, Adolph Philipse (1665–1750), died a wealthy bachelor with no children, so Philipsburg Manor was passed down to his eldest nephew, Frederick Philipse II. Shortly thereafter, Frederick posted advertisements to sell or lease his newly inherited property, including the enslaved people.

Related

Van Bergen overmantle (detail)

1730-1745

Attributed to John Heaton (active 1730-1750)

African, Native American and European people appear in this view of a colonial New York farm.

Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York, Museum Purchase, N0366.1954. Photograph by Richard Walker.

Negroes (“Negros”)

The list of “Negroes” on the inventory indicates that there were 23 enslaved men, women, and children who lived and worked at Philipsburg Manor in 1750. The decision to place the names of members of the enslaved community first on the list suggests that Philipse’s “human property” was considered to be his most valuable asset.

An actor portrays the work of a miller at Philipsburg Manor

Philipsburg Manor, Sleepy Hollow, New York.

Historic Hudson Valley.

Caesar (“Ceasor”)

Caesar was named first among those enslaved, suggesting that his work on the site was the most valuable to his enslaver. Because milling was crucial to the operation of Philipsburg Manor, and other primary documents note that the miller was an enslaved man, it is likely that Caesar was the name of the miller.

Silhouette of Young Men

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Sampson and Kaiser

Samson and Kaiser were most likely the two enslaved men responsible for farming the 750 acres surrounding the Upper Mills. On March 10, 1750, both men were sold to Lawrence Kortwright of New York City.

Silhouette of a Young Woman

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Abigal

The enslaved women at Philipsburg Manor were primarily responsible for butter production in the commercial dairy. Abigal was sold to Adolph Myer of New York City on March 22, 1750.

Silhouette of a Mother and Child

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Massy

Massy, along with her unnamed child, was sold to Cornelius Van Horne on April 19, 1750. The child was probably Hendrick, as he is the only child who does not appear in later documents.

Silhouette of a Mother and Child

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Dina

Dina gave birth shortly after the inventory was taken. Dina and her newborn infant were sold to Adrian Hoglandt of New York City on May 8, 1750.

Silhouette of an Elderly Man

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Men not fit (“fitt”) for work

This designation suggests that the appraiser considered these men too old or too injured to be productive laborers. However, they may have been highly respected within the enslaved community at Philipsburg Manor. Elders were esteemed as teachers and culture keepers throughout much of West Africa.

Cockfight

1840

After Henry Thomas Alken (English, 1785-1851)

Cockfighting was a brutal form of amusement in colonial taverns.

GRANGER — All rights reserved.

Venture

An elder on the 1750 inventory, Venture may have been the person of that name present at a cockfight held at Adolph Philipse's Manhattan home in 1737. This cockfight was organized by Cuffee, another enslaved man owned by Philipse, and attended by several enslaved men who were accused of arson and conspiracy in 1741.

Silhouette of a Young Boy

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Histπoric Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Boys

The ages for the boys listed range from 16 months to nine years old. Where are the 10-, 11-, and 12-year-olds? They were probably considered fully productive adults and would be listed as men. There was no “Girls” header in this inventory.

Silhouette of a Young Boy

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Sam

On April 19, 1750, a public auction, also known as a vendue, was held at Philipsburg Manor. Fifteen enslaved men, women, and children were advertised for sale. Three were sold that day, including Sam, an eight-year-old child who was sold, alone, to Abraham DePeyster of New York City.

Silhouette of a Father and Son

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Tom, Charles, Sam, Dimond, Ceasor

Many of the enslaved men and boys shared the same first names, suggesting fathers and sons, and the women listed in the inventory were certainly mothers in the community. However, men, women, and children were listed separately on the inventory because the law recognized the enslaved only as property and not as family units.

Silhouette of a Young Girl

A silhouette was one way a person's likeness was captured in the 18th century. Historic Hudson Valley has commissioned silhouettes to represent individuals of whom no other portrait is known to exist.

Betty

Because the Philipse family rarely visited Philipsburg Manor, girls were not needed there for domestic labor and adult enslaved women were responsible for the commercial dairy. After reaching a certain age, young enslaved girls were most likely moved to Frederick Philipse’s larger home in Yonkers for training in housework. Within a year, Betty was moved to Yonkers.

Cattle

Milk cows were included among the livestock listed in Adolph Philipse's probate inventory. The cows provided the raw milk essential to the commercial dairy run by the enslaved women at Philipsburg Manor.

Historic Hudson Valley.

Cattle

After listing the enslaved community, the inventory continues for another six pages, listing the remainder of Philipse’s possessions at the Upper Mills including livestock, luxury goods, furniture, and so on.

Tumbler

1687-1702

Unknown, probably American

A piece of silver engraved with a stylized "VF," the brand of Frederick Philipse.

Historic Hudson Valley.

Silverware

Although the Philipse family rarely stayed at Philipsburg Manor, they owned enough silverware to keep several silver tankards, mugs, utensils, and a pepper box in the Manor House, which suggests their material wealth.

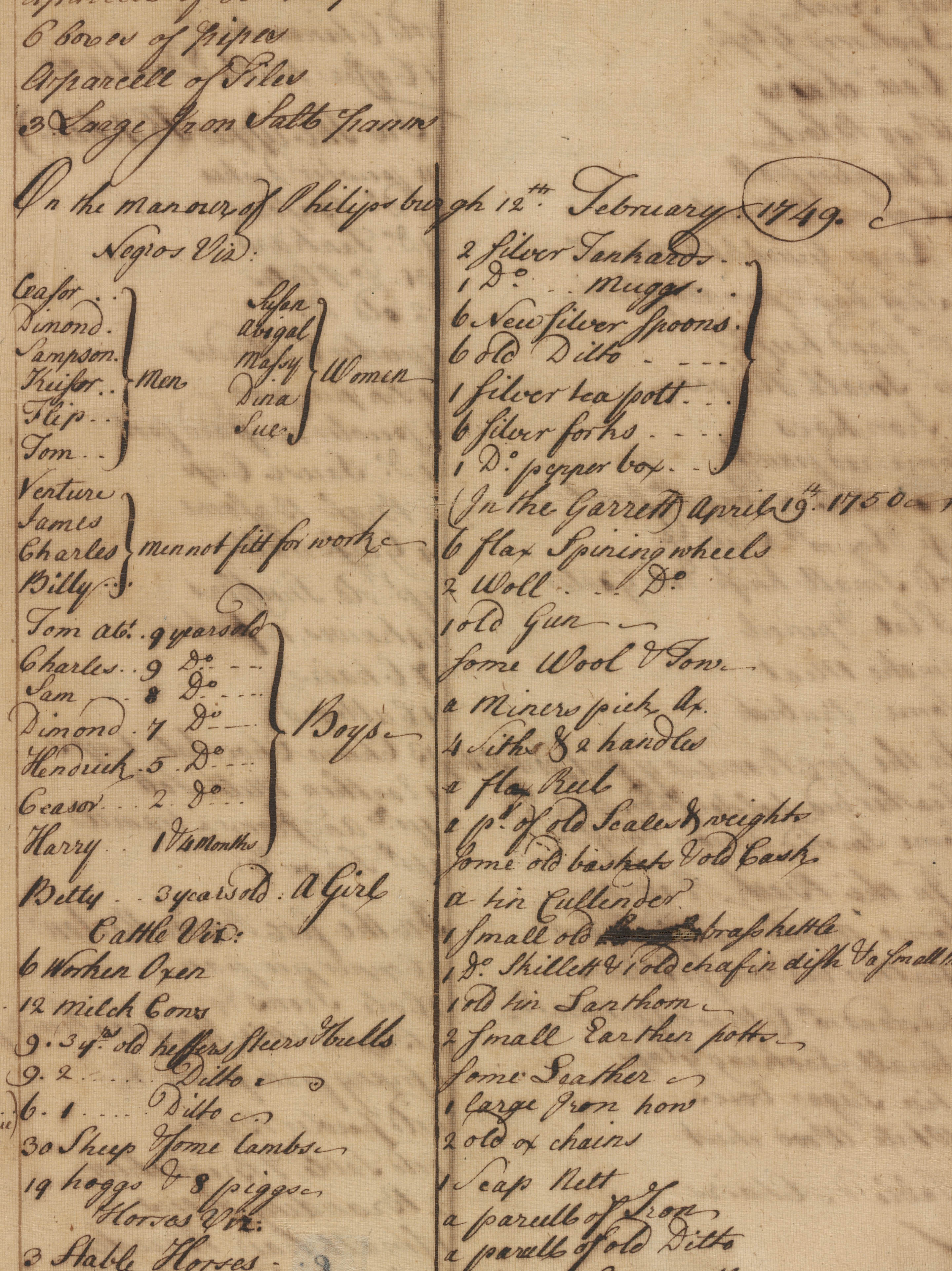

Inventory of all and Singular the goods, Rights Chattels & Credits of the Estate of Mr. Adolph Philipse Deceased vizt:

On the manour of Philipsburgh-12th February 1749/50

Negros Viz:

Men

Ceasor

Dimond

Sampson

Kaiser

Flip

Tom

Men not fitt for work

Venture

James

Charles

Billy

Women

Susan

Abigal

Massy

Dina

Sue

Boys

Tom abt 9 years old

Charles 9 Do

Sam 8 Do

Dimond 7 Do

Hendrick 5 Do

Ceasor 2 Do

Harry 1&4 months

A Girl

Betty ...3 years old

Cattle Viz:

(old)

6 worken Oxen

12 Milch Cows

9 3yr old heffers Steers & bulls

9 2 ditto

(all dead 'fore ye Vendue')

6 1 ditto

30 sheep & some lambs

19 hoggs & some piggs

Horses Viz:

3 Stable Horses

3 horses in the woods

17 Mares & young horses

A page from the probate inventory of Adolph Philipse

1750

Joseph Reade (English, born New York, 1694-1771)

This single page from the lengthy inventory of Adolph Philipse's estate includes the names of the enslaved individuals living at Philipsburg Manor, Upper Mills.

Adolph Philipse estate records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

An actor portrays the work of a miller at Philipsburg Manor

Philipsburg Manor, Sleepy Hollow, New York.

Historic Hudson Valley.

Caesar (“Ceasor”)

Caesar was named first among those enslaved, suggesting that his work on the site was the most valuable to his enslaver. Because milling was crucial to the operation of Philipsburg Manor, and other primary documents note that the miller was an enslaved man, it is likely that Caesar was the name of the miller.

To continue please visit People Not Property on a larger screen or horizontal device to fully experience this feature.