Stories About Marriage

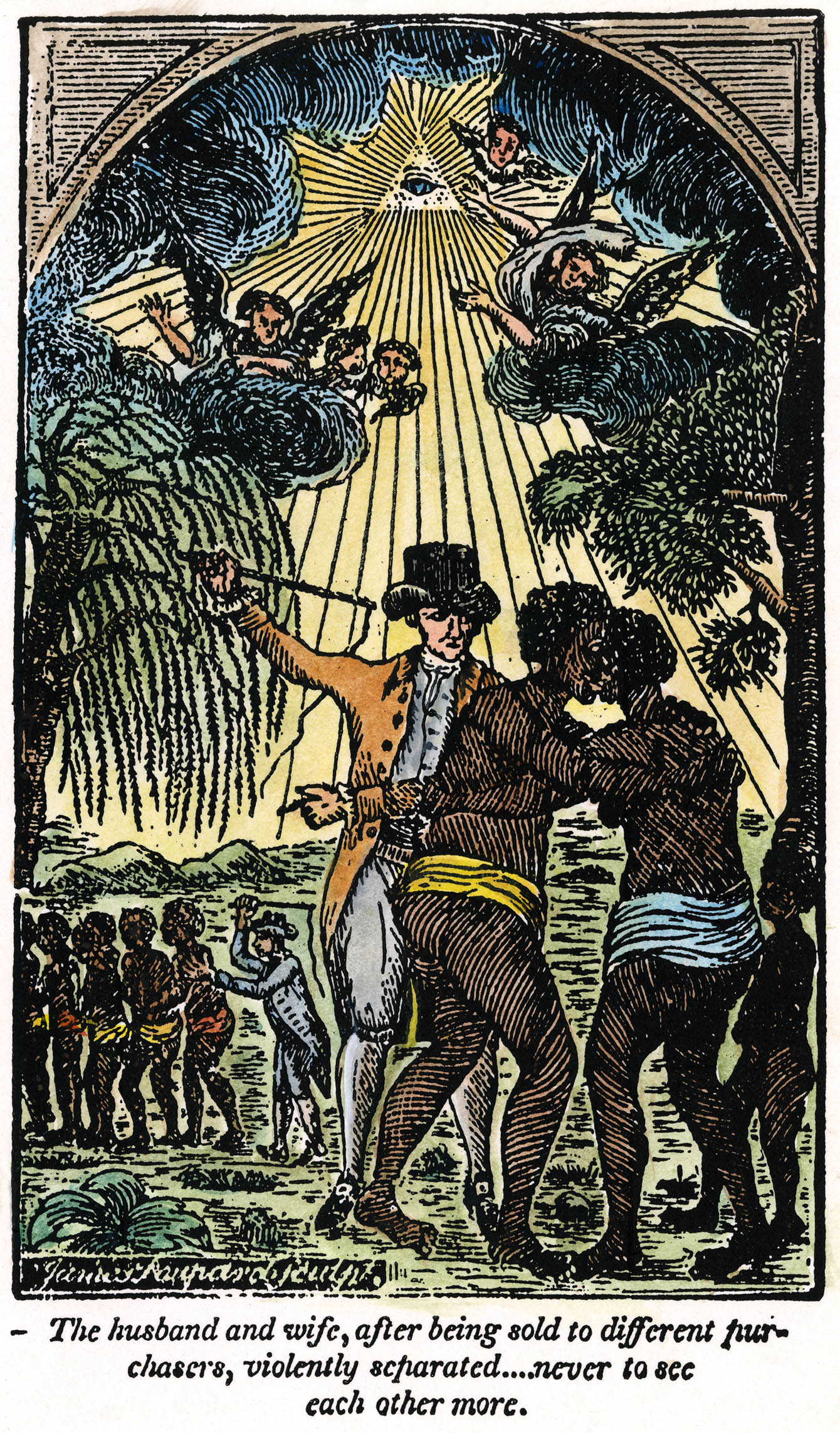

Enslaved men and women faced grave obstacles when they attempted to marry. Their legal status as property made it impossible for them to enter into an official contract, and if they were held by different enslavers—not uncommon in the North, where there were a relatively small number of enslaved men and women in individual households—it was extremely difficult for them to start a life or a family together.

Yet despite these challenges, enslaved men and women did fall in love and marry, even if their union was not legally or religiously recognized.

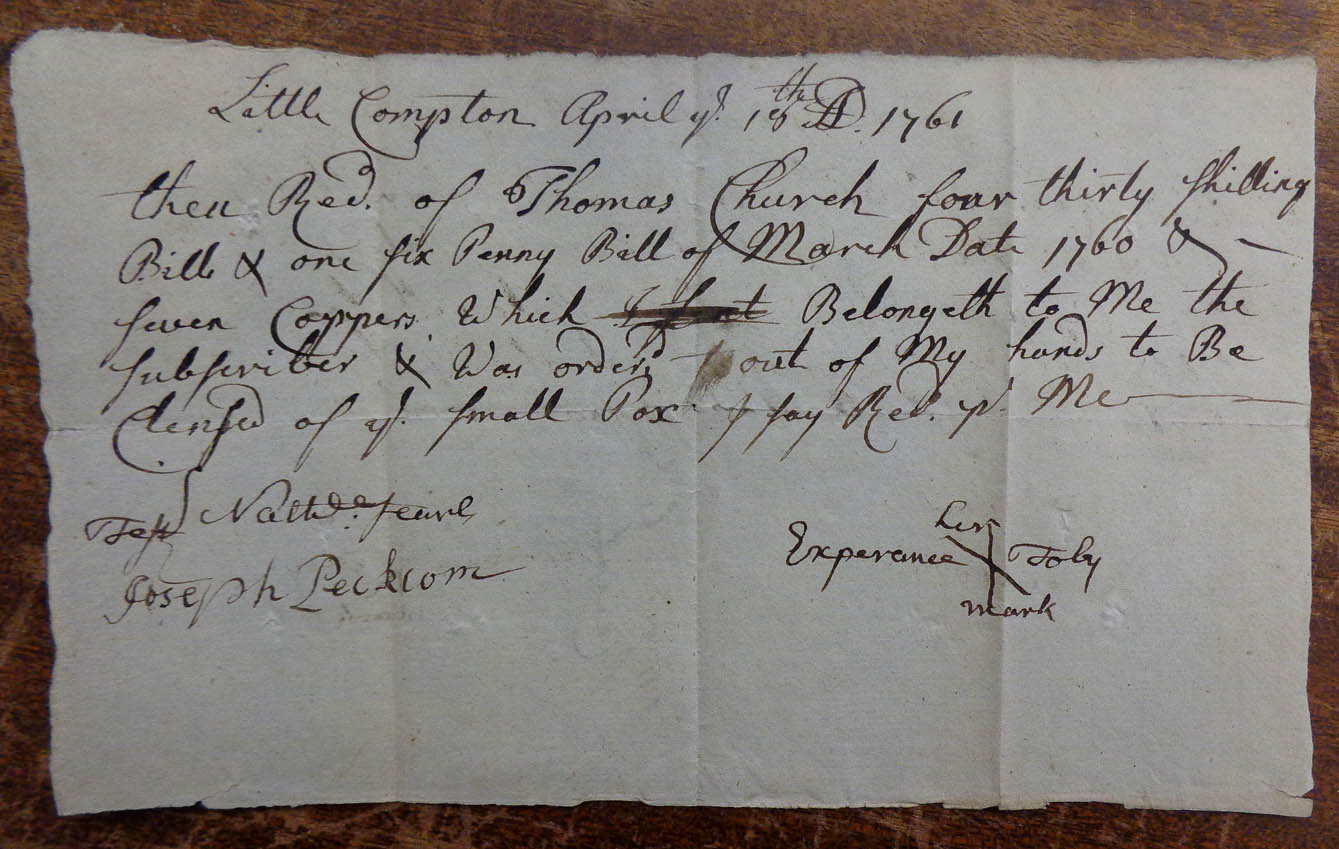

In Little Compton, Rhode Island, documentation for the enslaved man Sampson and his free-born Native American wife Experience Tobe provides a glimpse into the difficulties for a married couple of mixed status. Born in 1720, Sampson was sold to a man named William Shaw before his second birthday. Years later, Sampson negotiated a plan to purchase his freedom from Shaw for £150, about three years’ wages for a tradesman. In addition to paying Shaw, Sampson’s agreement required him to complete certain tasks for Shaw for the duration of his lifetime.

Sampson subsequently married Experience, and the couple’s two daughters shared their mother’s free status.

While Sampson was still saving money towards his freedom, he left Rhode Island to serve in the French and Indian War. When he returned to Little Compton, he was blamed for an outbreak of smallpox and he and his family were quarantined by the town. They were charged an excessive amount for their medical care, and the funds they had been saving toward the purchase of Sampson’s freedom were confiscated by town officials.

Lacking resources and unable to work, they quickly fell behind on this new debt. As a result, their daughters were “bound out,” or indentured involuntarily, to work for local residents.

When the couple attempted to sue for the return of their money, possibly to pay for the release of their daughters, the court refused. Citing the letter of agreement between Sampson and his enslaver, the court instead awarded the money to Shaw as a payment towards Sampson’s liberty.

Court records say nothing further about the fate of Sampson and Experience, and it is unclear whether Sampson was ever able to complete the purchase of his freedom. The hardships endured by this couple illustrate how one person’s status as property could have dire consequences for an entire family, even for those who had been born free.

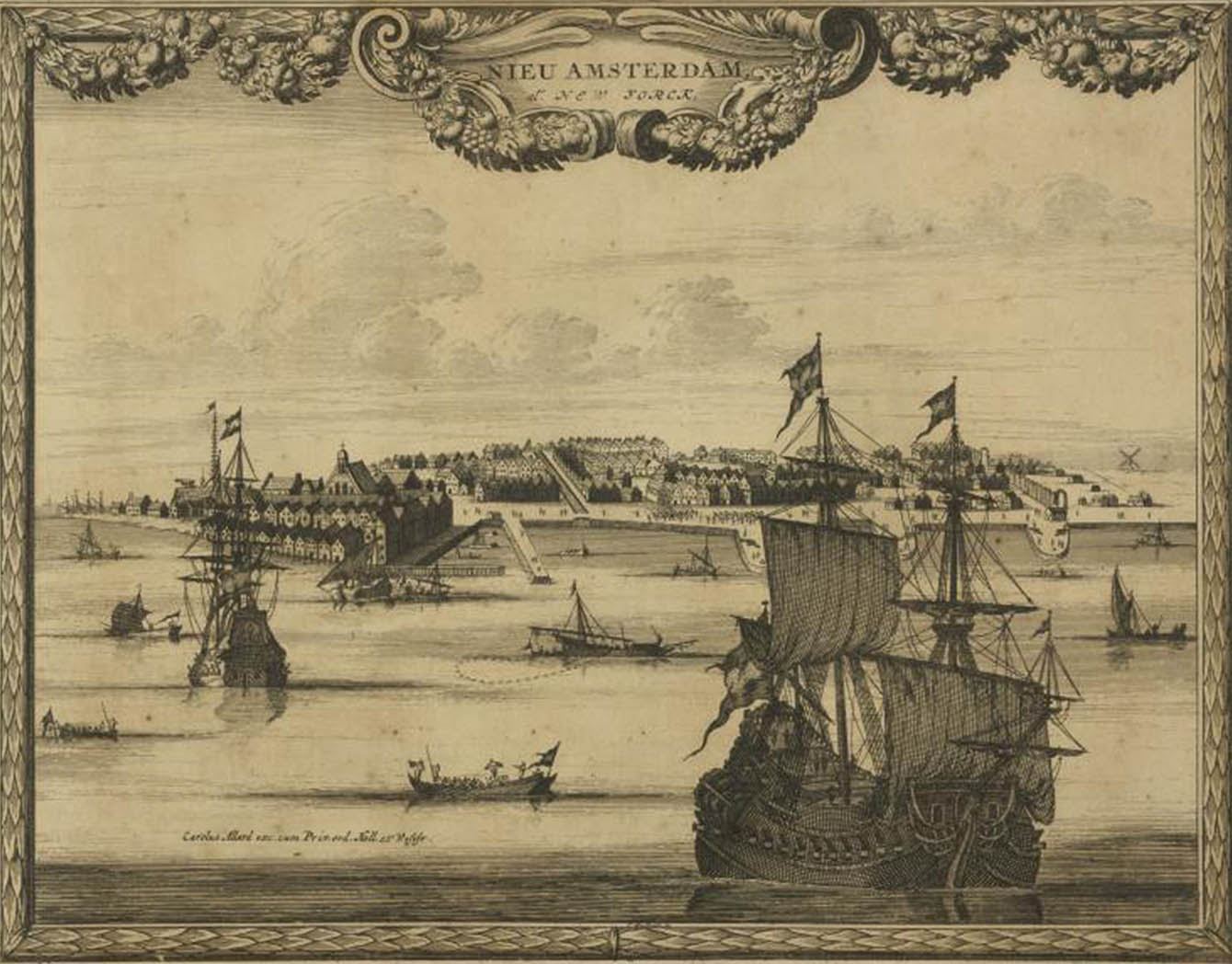

Before Dutch legislators formally defined and codified slavery, enslaved men and women in New Amsterdam had enjoyed a measure of freedom in the Dutch Reformed Church. In the early 17th century, Creole men and women had the freedom to register their marriages and seek baptism for their sons and daughters in the church. But as the custom of enslavement shifted into formal laws, these activities were more tightly controlled. Enslaved men and women, as property, were restricted from entering into contracts of any kind without the permission of those who held them in bondage.

The complexity of marriage under enslavement is reflected in the 18th-century records of Christ Church in Philadelphia, where the names of couples who took marriage vows appear. Enslaved brides and grooms are described in these records as marrying “by consent” of their owners. However, these marriages were not always recognized as a legal union, and men and women could still be easily separated by their enslavers. In many cases, husbands and wives were held by different enslaving families and always lived apart.

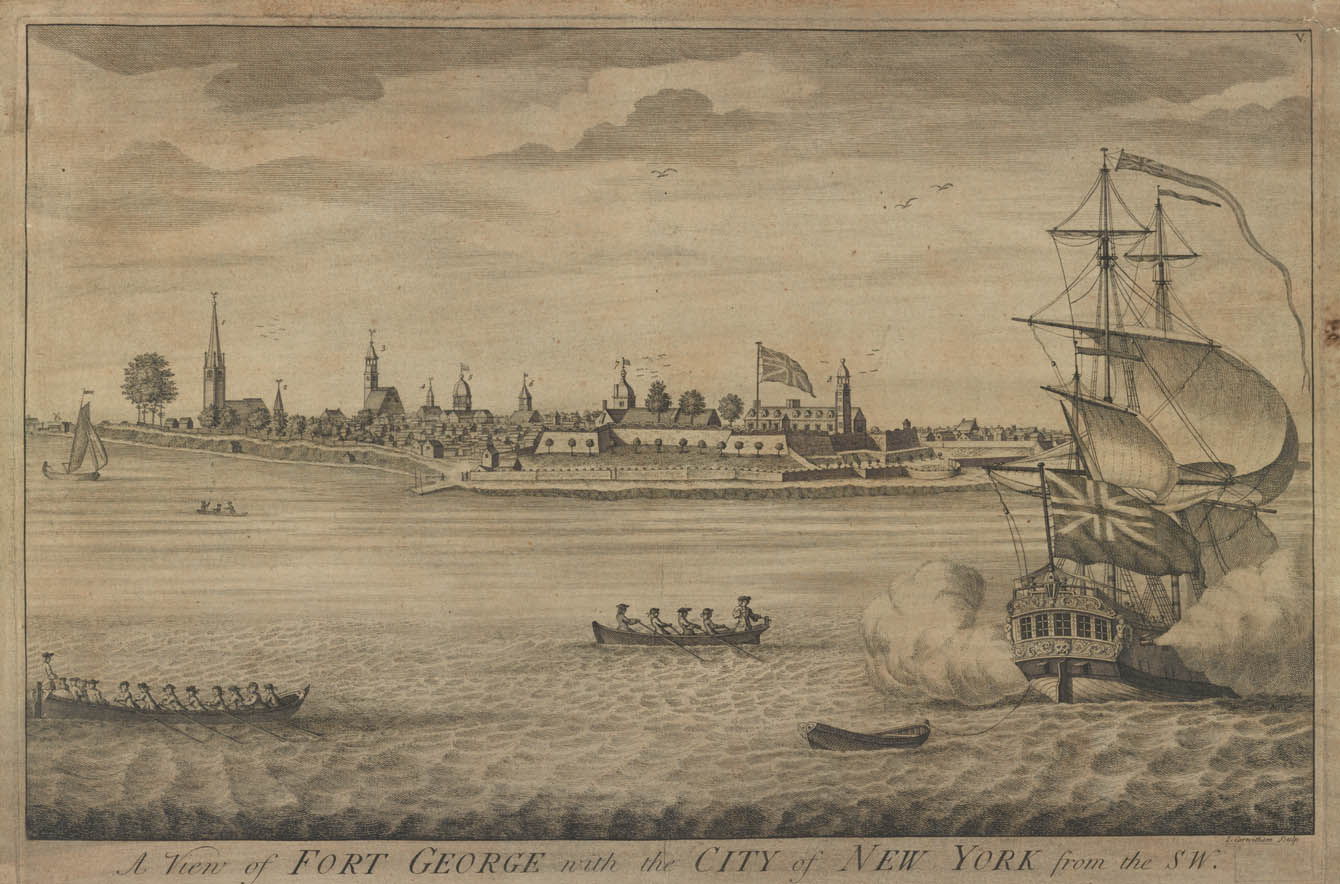

One couple’s inability to visit one another resulted in violence. Quack was enslaved by John Roosevelt of New York City. His wife Barbara served as the enslaved cook of Governor George Clark within the Governor’s residence at Fort George. When Quack attempted to visit Barbara at the fort, he was refused. Transcripts of his trial note that this denial so angered Quack that he volunteered to burn down the fort as part of the 1741 insurrection plot. The records are unclear about whether Barbara could visit Quack while he was in jail, but it is likely that Barbara witnessed his execution later that spring.

Enslaved couples established committed relationships, whether approved by a church or not. Advertisements for fugitives confirm this. A 1764 ad about “a Negroe Woman named Betty” noted that “she has a husband at Mr. Bard’s Iron-works in Mount-Holly, and it is thought she keeps thereabouts.” Other enslavers dismissed the legality of enslaved marriages. A New Jersey ad for “Sarah,” stated that she was "apprehended in the first Maryland regiment, where she pretends to have a husband.”

Enslavers often disregarded the bonds of marriage made by those they held, but these ads suggest that fundamental partnerships were worth considerable risk to the people who cherished them.