More Stories About Fighting Back

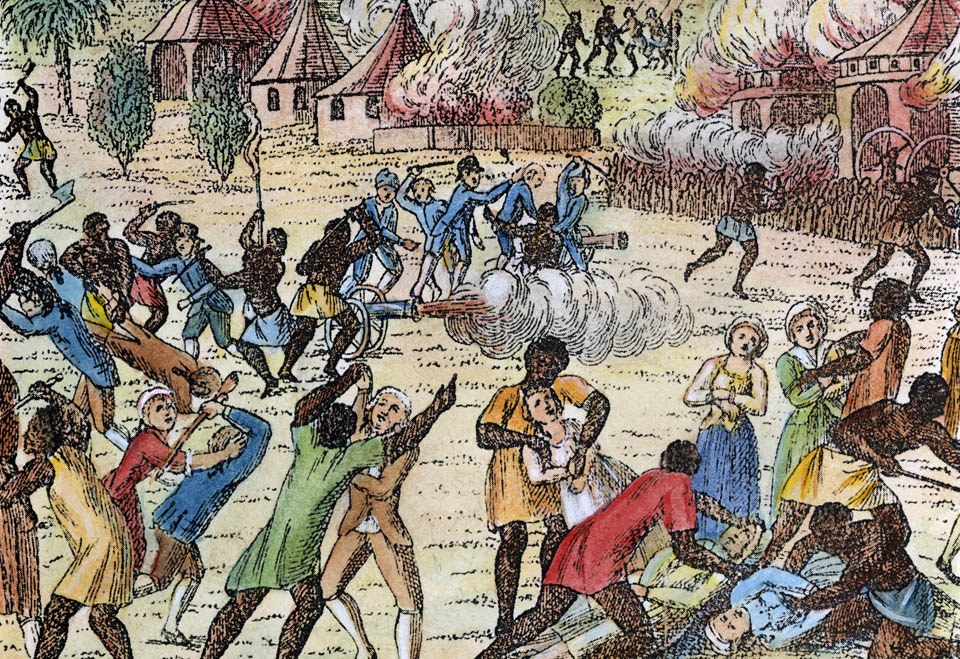

The New York Conspiracy of 1741 wasn’t the only plot to rebel that took place in the colonial North. In fact, it wasn’t even the only insurrection in New York. Desperate circumstances motivated some enslaved men and women to take violent action. Enslavers, fearing conspiracy and mass revolt, delivered the harshest punishments (including death by execution) for any act of rebellion, real or suspected. They used the colonial legal system to reinforce this radical imbalance of power.

Nevertheless, many enslaved people still chose to fight back.

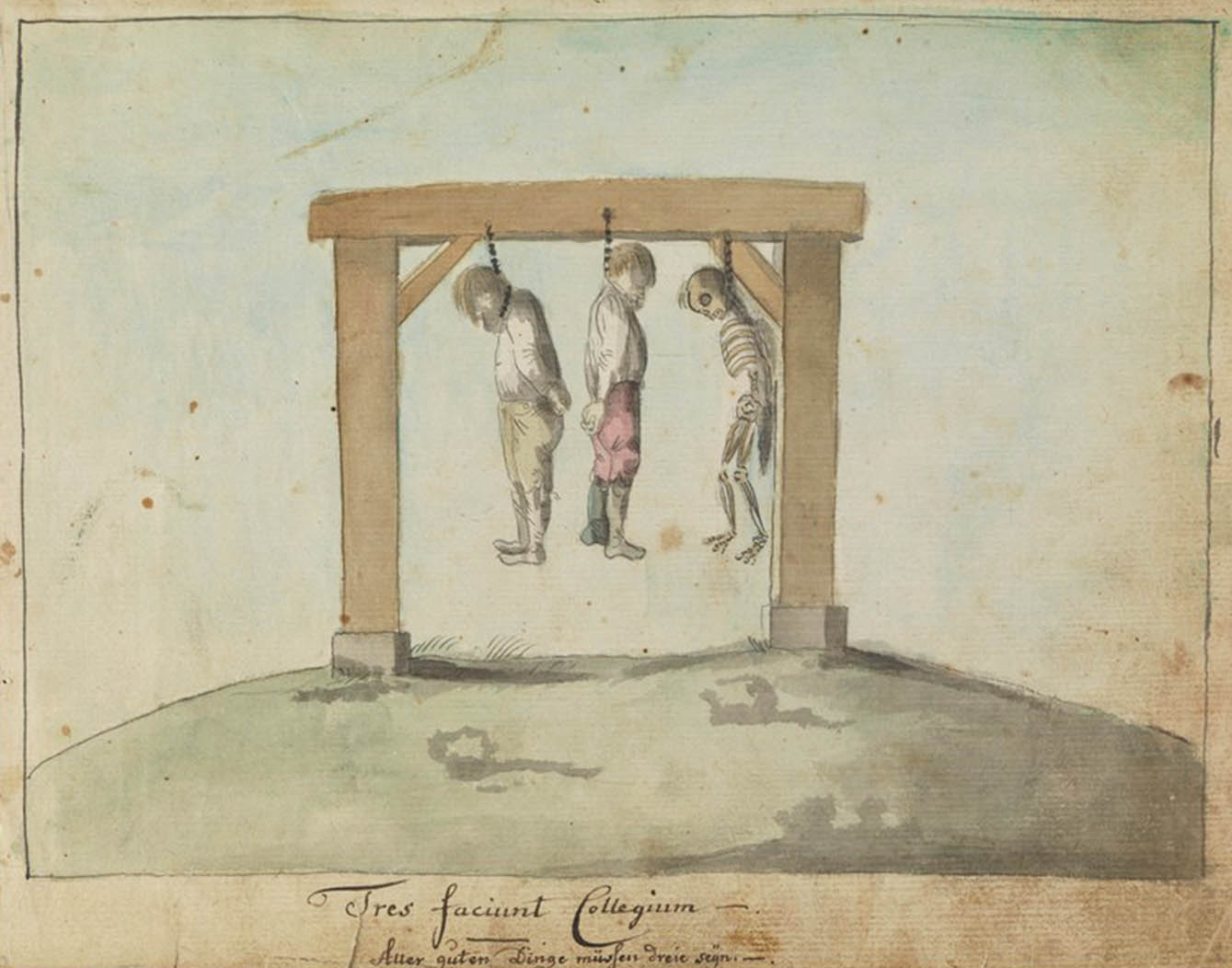

During the evening of April 1, 1712, several enslaved people allegedly set fire to a house in New York City. When white residents arrived to fight the blaze, the conspirators brandished muskets and knives, killing nine. Within two months, twenty-five enslaved people had been convicted and sentenced to death for these crimes: twenty were hanged; one was broken upon the wheel; one was hung in chains “without sustenance” until dead; and three others were burned to death.

This brutal punishment was clearly meant to warn the enslaved community not to consider rising up in violence again.

In the spring of 1741, less than one month after the suspicious fires occurred in New York City, residents of Hackensack, New Jersey, just eight miles northwest of Manhattan, panicked as seven barns in town burned. Two enslaved men, Jack and Ben, were arrested. One fired a musket at witnesses as he came out of a burning barn, while the other was found loading a gun. Military patrols kept watch over the nervous white residents at night for weeks after the events.

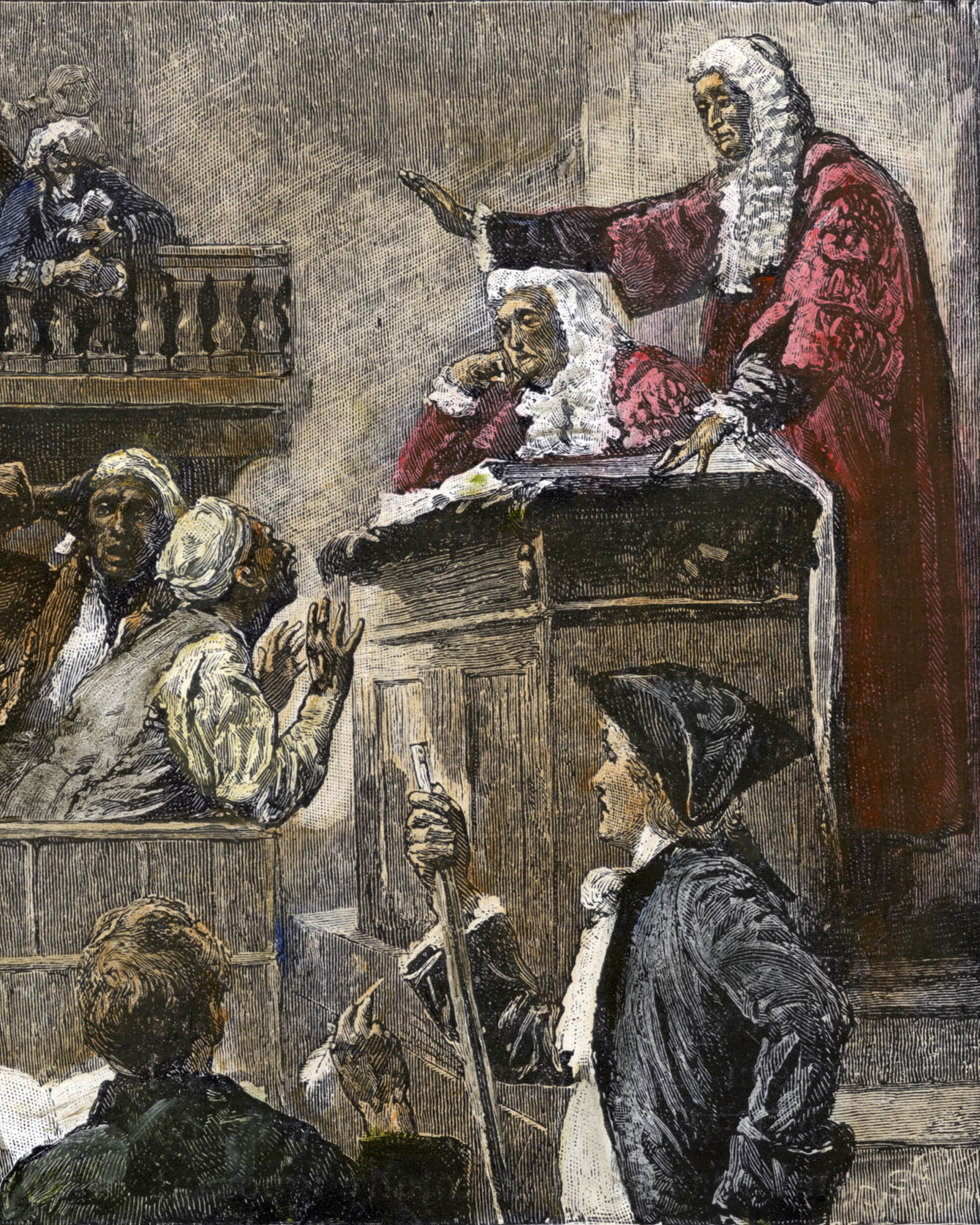

According to a contemporary account of the event, Jack and Ben were hastily “tried, convicted, and burnt at the stake: the former confessed that he had set fire to three of the barns; the latter would confess nothing.”

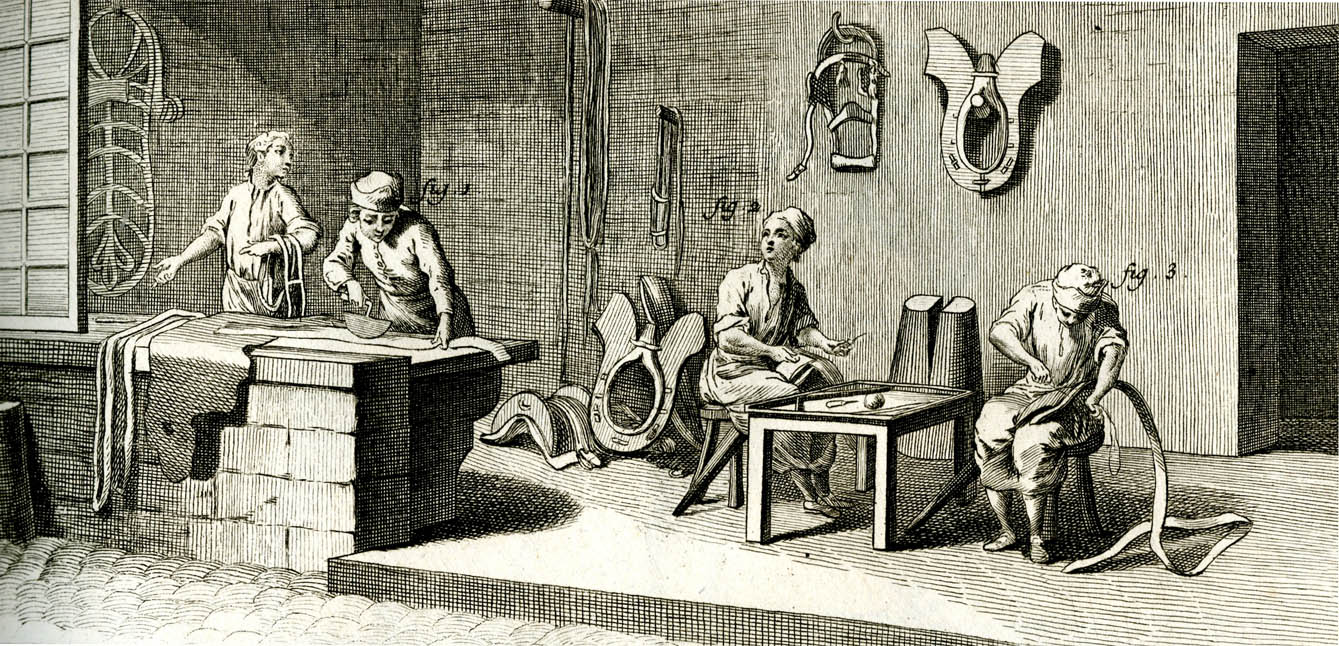

When enslaver John Codman separated a man named Mark from his family in Boston, Mark set fire to Codman’s saddle-making workshop. Court records show that Mark hoped the financial loss from the fire would cause Codman to sell him so that he could return to Boston. However, Mark was not sold, so he and two enslaved women, Phoebe and Phillis, took more drastic action. In July 1755, Codman was found dead in his home from arsenic poisoning.

Mark and Phillis were accused of murder, tried, and sentenced to die. Phillis was burned at the stake, while Mark was executed by hanging, after which his body was tarred and suspended in irons from a gallows in Charlestown Common. The fate of Phoebe was not reported.

Mark’s body remained on display as a stark reminder of the fatal consequences of defiance. Twenty years later, Paul Revere passed the spot of Mark’s execution during his famous ride, noting: “After I had passed Charlestown Neck, and got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on Horse back.”

Even when confrontations were instigated by enslavers, they could still result in fatal consequences for those they held in bondage.

In August 1735, an enslaved man named Jack was accused of beating his enslaver, Peter Kipp, of New Jersey. The case was heard in court two days later. Kipp and other family members testified that Kipp first struck Jack and that Jack “resisted and fought with his master, striking him several blows” and threatening the family. A panel of justices and freeholders decided Jack’s fate quickly—that he be put to death by burning the following morning.

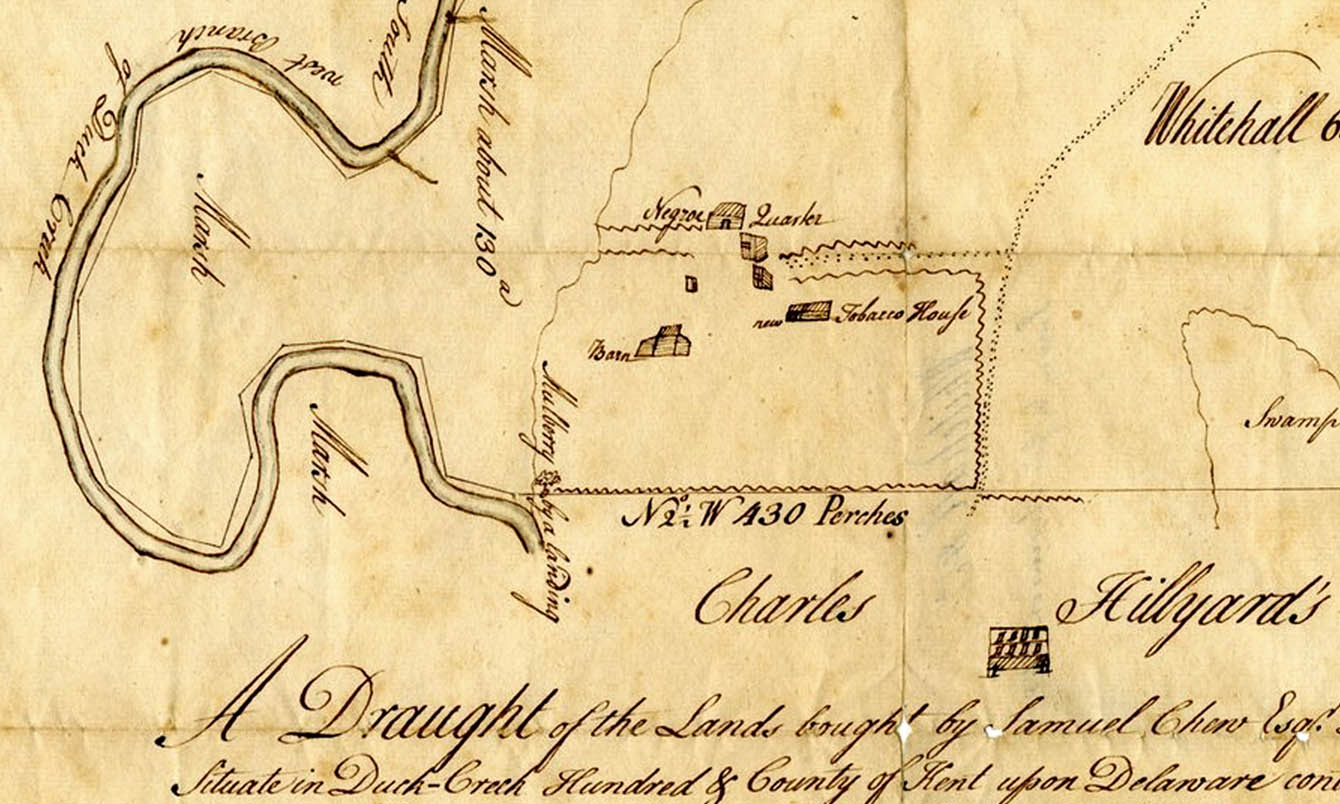

Not all violence resulted in death, but fighting back always had consequences. In 1795, Pennsylvania planter Benjamin Chew received a letter from his overseer George Ford. Ford reported that he had been “...beatin by clubs till I was blody as a bucher" by Jim and Aaron, two enslaved men on Chew’s plantation. Ford asked Chew for permission to “correct,” or punish, the men, and later whipped them with the assistance of another white man. The incident showed a calculated risk by Jim and Aaron. They were willing to endure pain—or worse— to inflict injury on the man who represented their enslaver’s interests.