Stories About Purchasing Freedom

Accounts of enslaved individuals purchasing their freedom rarely describe the enormous challenges they faced to do so. The colonial legal system did not outline this process. Additionally, most enslaved people, particularly women, could not earn the income necessary to buy their way out of an unjust system. Few were able to negotiate with their enslavers for terms that they could afford, nor was there a guarantee that enslavers—or the descendants of enslavers—would always honor an agreement. These arrangements, easily overturned, were never set in stone.

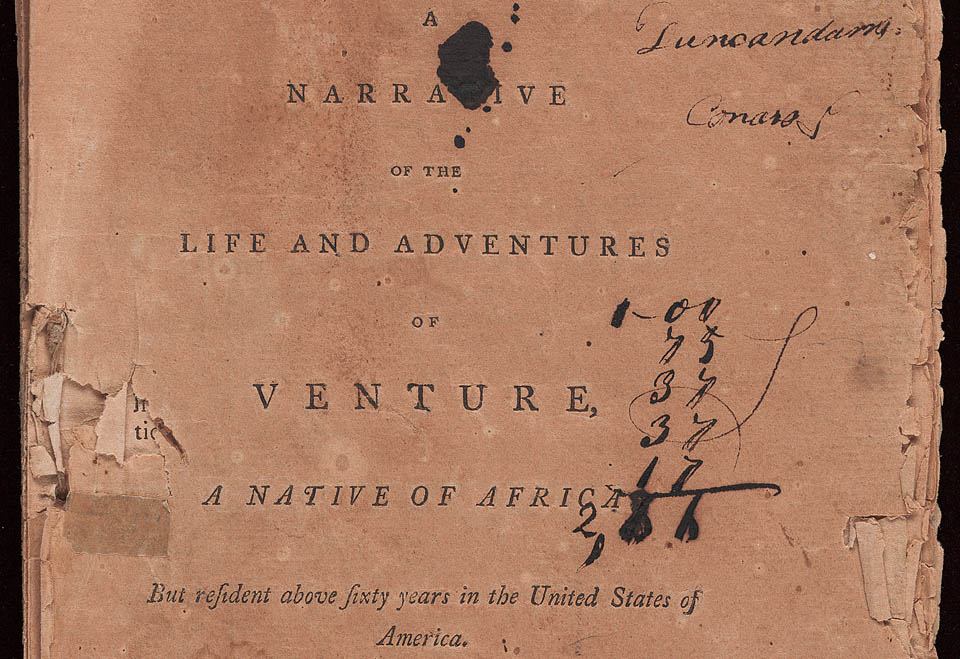

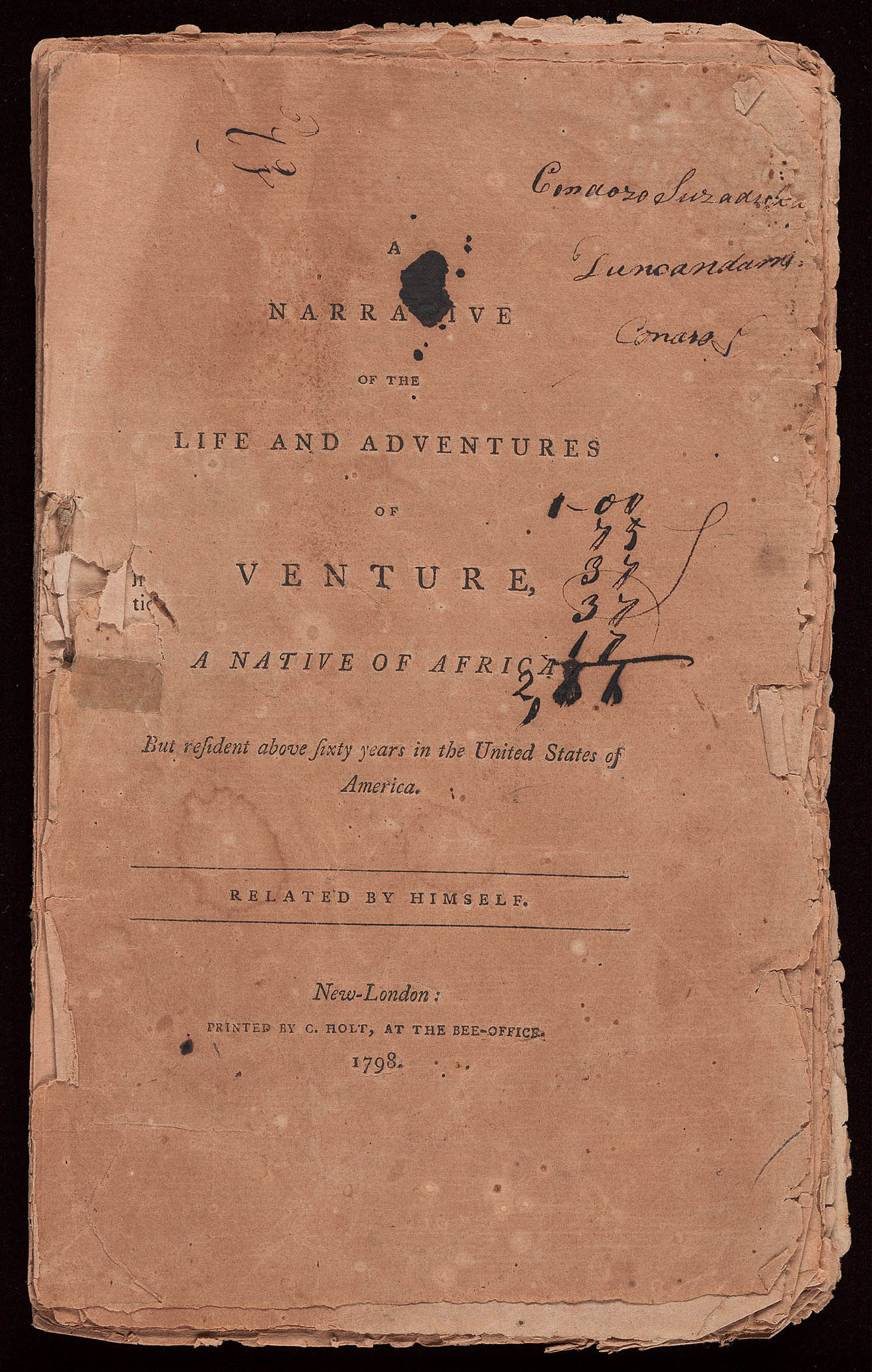

Connecticut’s Venture Smith was among the first to publish an autobiography documenting his enslavement in colonial America. Smith’s narrative details his fight for freedom after enduring decades of hardship, numerous beatings, and a foiled escape.

Born Broteer Furro in the region now known as Ghana, Smith was captured at the age of six, separated from his family, and sold to Robertson Mumford for four gallons of rum and a piece of calico cloth. Mumford renamed him Venture.

In 1760 Venture was sold to his third enslaver, Col. Oliver Smith, who was open to his proposal to purchase himself if he met Col. Smith’s purchase price.

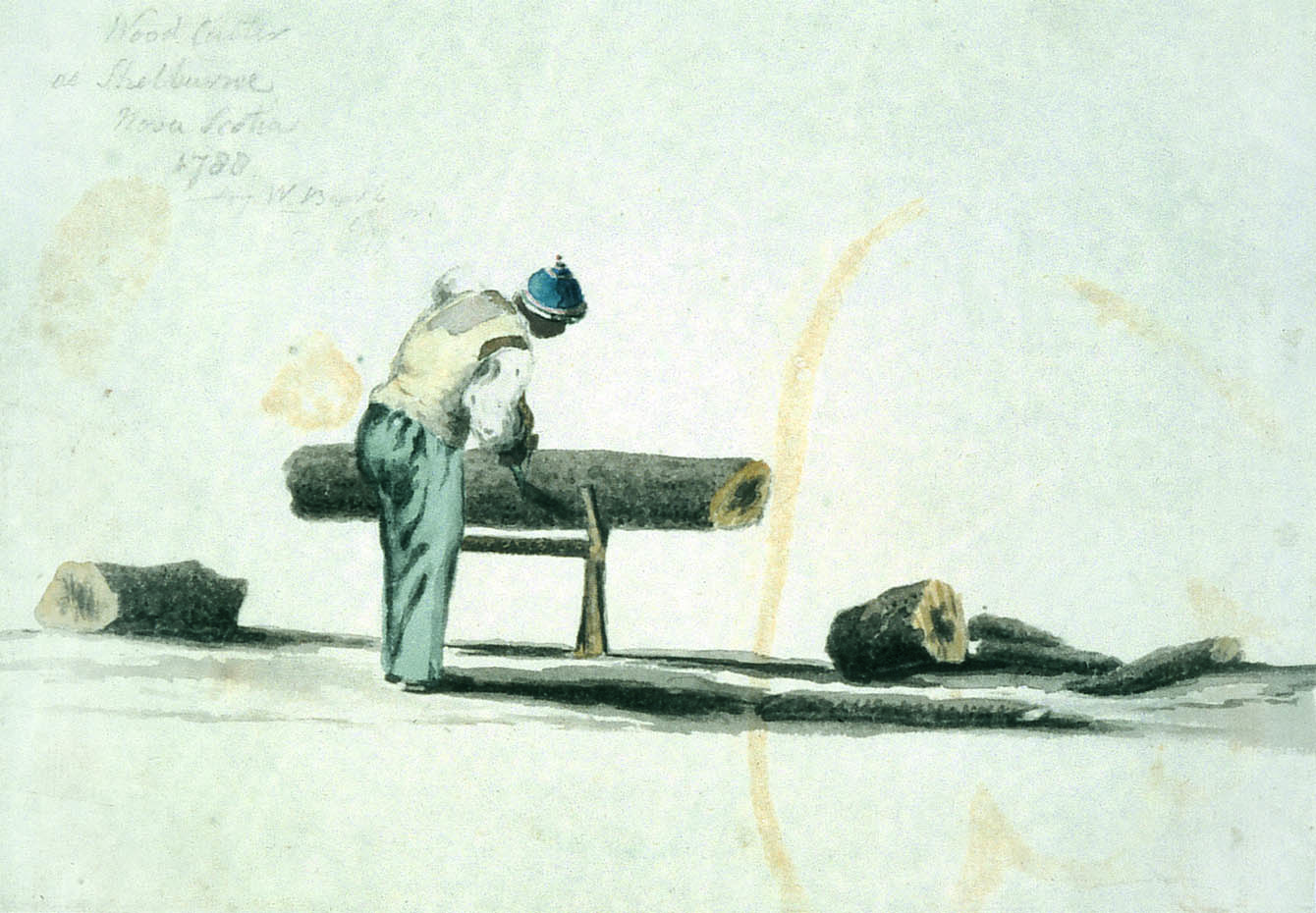

After completing his daily chores, Venture, with Col. Smith’s consent, hired himself out to local farmers, earning wages by cutting firewood, threshing grain, clearing land, and piloting fishing excursions. After five grueling years of labor, Venture paid Col. Smith £71 for the purchase of his freedom. He was 36 years old.

For the next 11 years, Venture Smith, as he called himself, continued working to free his family. His hard work enabled him to free two of his sons, his wife, his daughter, and three unrelated enslaved men.

Venture Smith’s life, however, was not without hardship. His oldest son, Solomon, died at age 17 on a whaling excursion. His daughter, Hannah, died of illness only one year after she was freed.

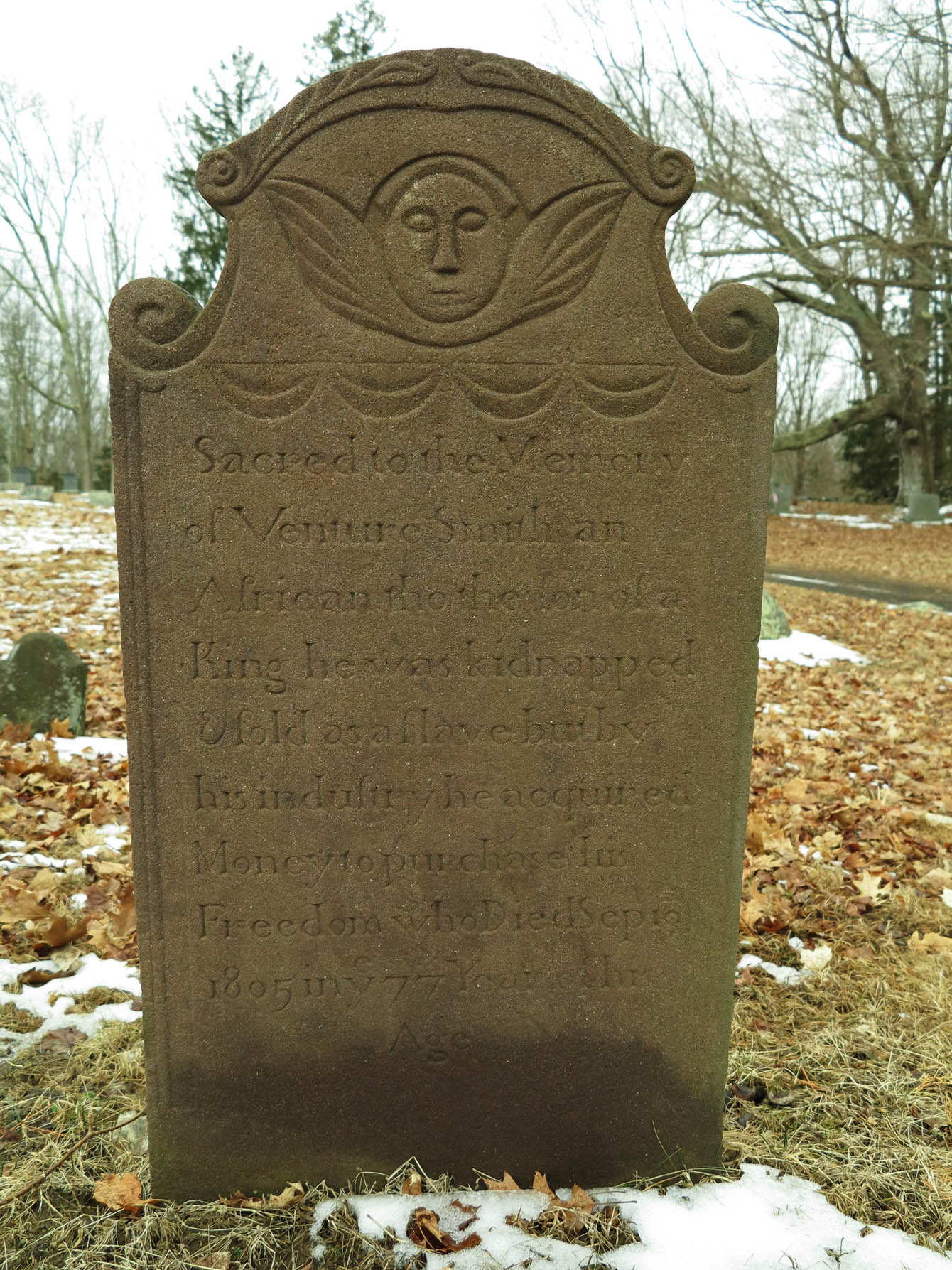

Venture Smith died in 1805 at the age of 77. He and his family are buried in East Haddam, Connecticut. Their gravestones attest to Smith’s determination to free his family.

Often, the process of negotiating for the purchase of one’s freedom was met with strict restrictions or lengthy labor requirements after obtaining freedom.

In 1805, Yat, an enslaved man owned by the Glen family of Schenectady, New York, negotiated a lengthy agreement allowing him to purchase his freedom for $90 over the following six years. The agreement, however, was conditional, stating that Yat must continue to serve his enslavers “faithfully” for those six years.

The Glen family’s arrangement with Yat illustrates the power of the enslaver to set arbitrary or even impossible terms for enslaved individuals seeking freedom. Yat previously earned extra money by hiring himself out to local neighbors as a fiddler, but under the terms of his agreement, he was permitted to do this only on his days off, which amounted to just 10 days a year. Yat was allowed to visit his wife, who was enslaved elsewhere, just one day each month. The slightest infraction, or the inability to pay the purchase price, would void the agreement.

Roco and Sue were a couple enslaved by John Pynchon of Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1695, they entered into an agreement with Pynchon to purchase their freedom.

In exchange, Roco and Sue agreed to supply their enslaver with “twenty five Barrels of good cleane pure Turpentine… & Twenty one barrels of Good merchantable Tarr” within a year’s time. If, however, “the Summer be so cold that the Turpentine cant run,” Pynchon agreed to give them another year to make good on the agreement.

Neither Roco nor Sue were listed in Pynchon’s probate inventory of 1705, suggesting that they succeeded in their quest.

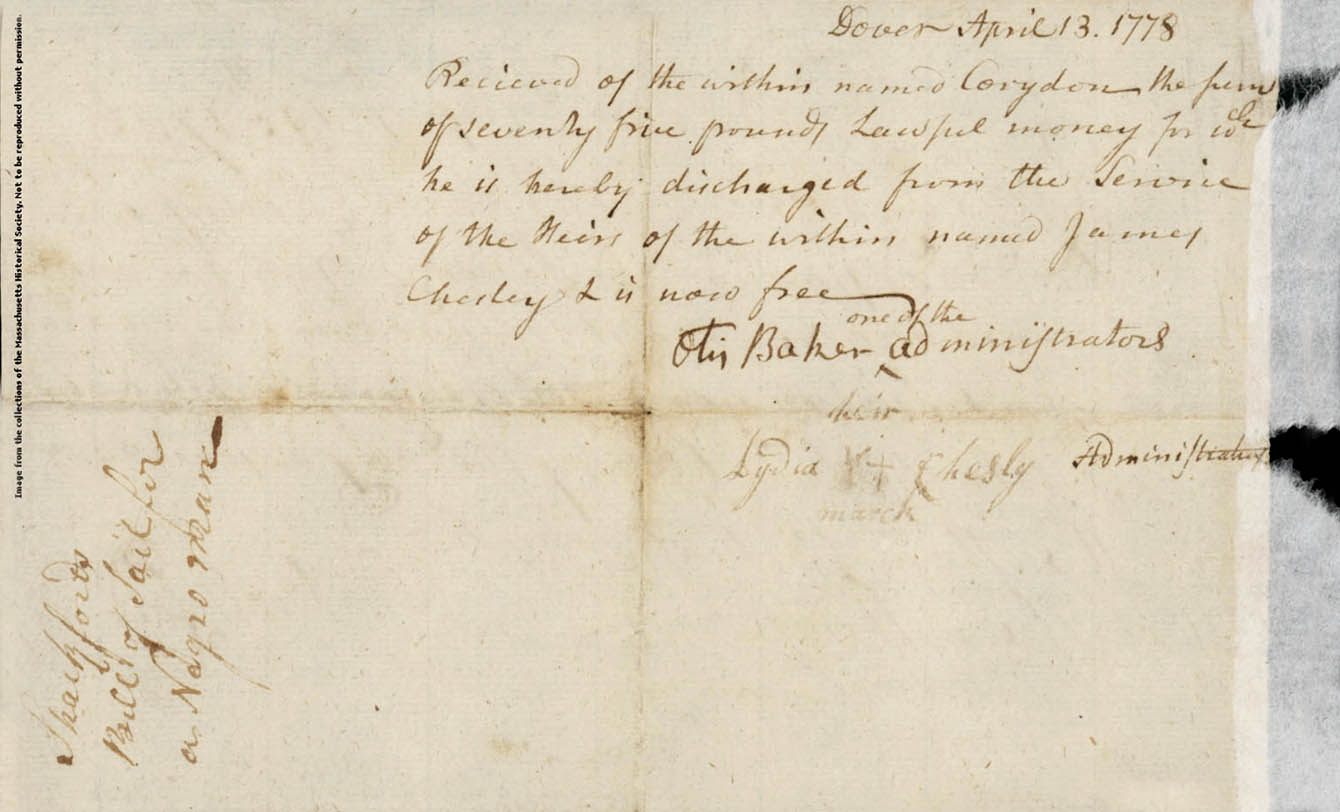

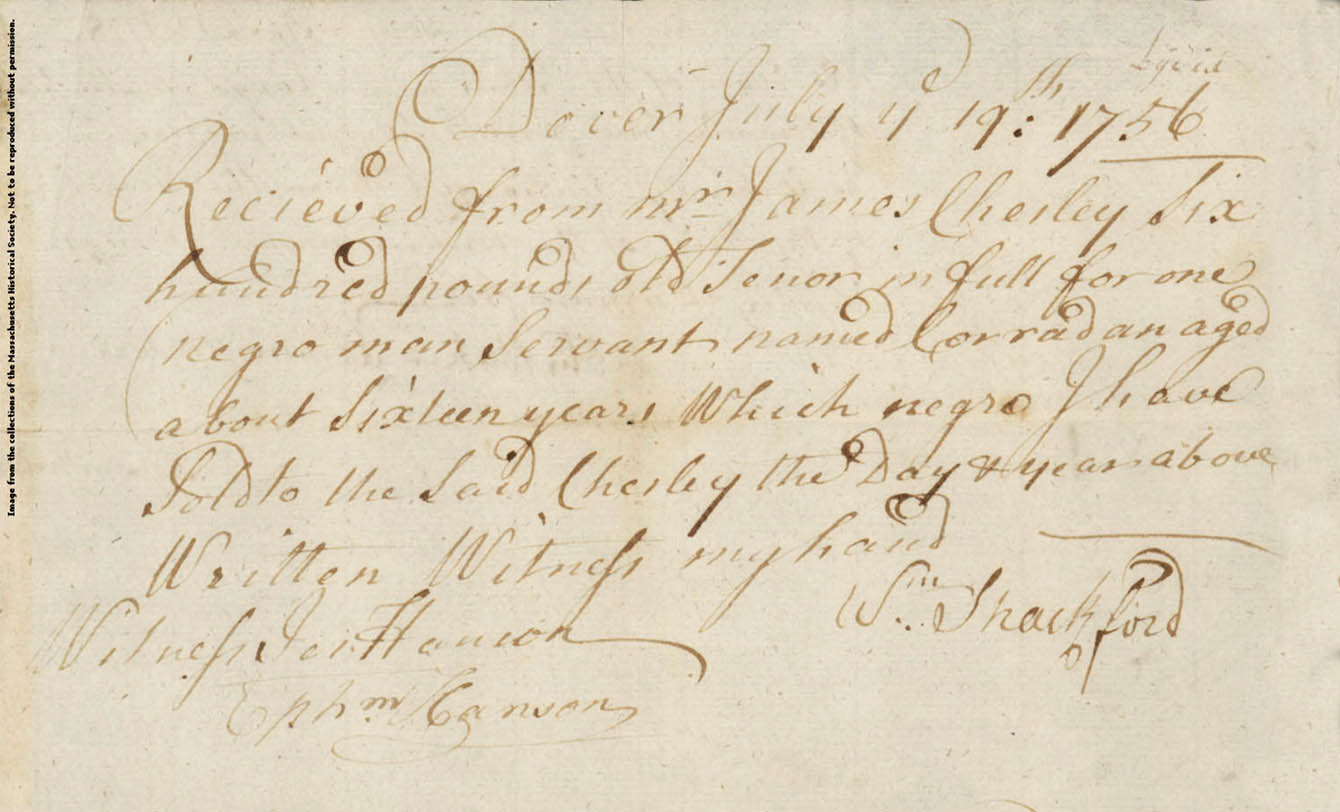

Everything that historians know about Corradan [Corydon], an enslaved man from Dover, Massachusetts, comes from a single, two-sided document. On one side, dated July 19, 1756, is a hand-written bill of sale that records the purchase of 16-year-old Corradan by James Chesley.

On the other side of the document, dated April 13, 1778, is a note by James Chesley's heirs, stating that “Corydon [for] the sum of seventy five pounds… is hereby discharged from the Service of [Chesley’s] heirs… & is now free.”

At 38 years old, Corydon had successfully purchased his freedom from the Chesley family. While no further information is available about Corydon, this record, at once a bill of sale and a receipt for freedom, speaks to his endurance in the face of a deeply unjust system.