More Stories About Running Away

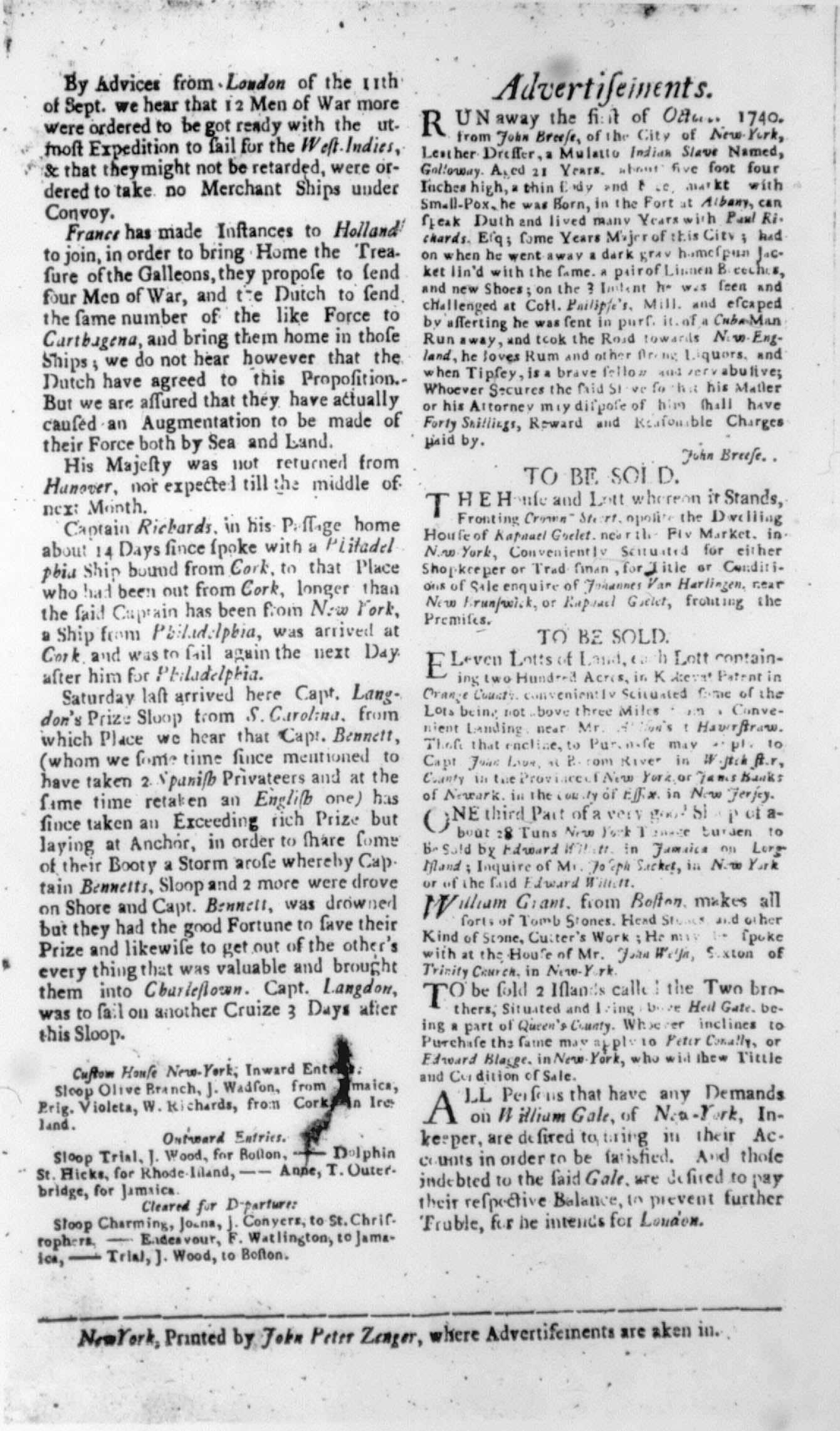

Every enslaved person who chose to escape did so for unique reasons. Advertisements for “runaway slaves” cannot convey why an individual would make such a dangerous and often temporary choice. Nevertheless, they provide a rich resource for learning about the people who self-emancipated and offer clues as to why. Reuniting with family, leaving an abusive enslaver, or causing economic harm to their enslavers were among the motivations for thousands of individuals who chose to run away. However, because slavery was still legal throughout North America at this time, permanent freedom was rarely attainable.

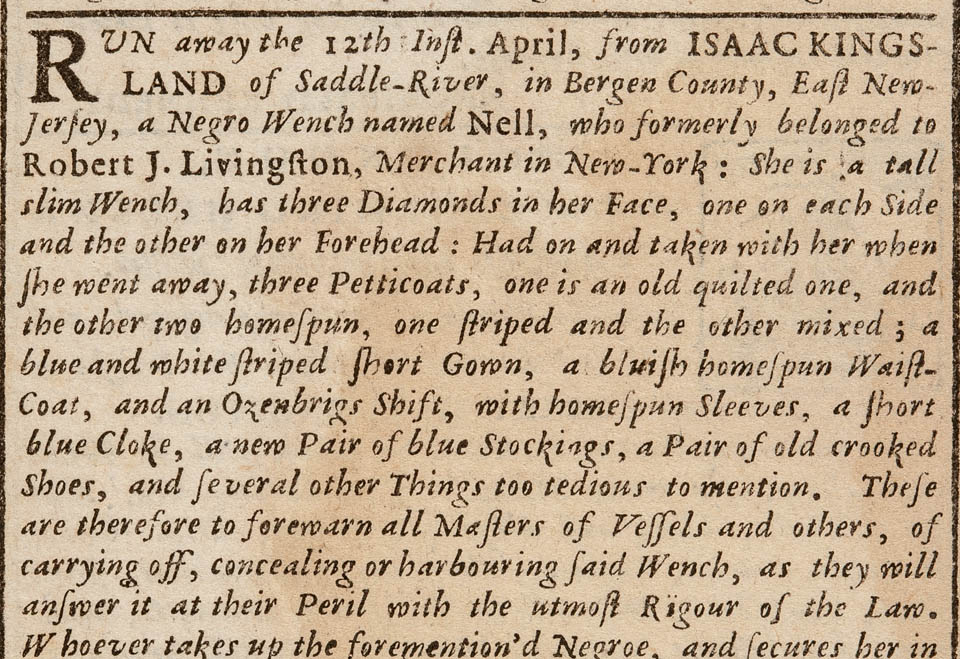

Nell ran away from two different enslavers within three years. The New York newspaper ads for her return provide clues to her life. The ads describe three diamond patterns on her face, “one on each side and the other on her forehead.” These marks are found in several regions of Gabon, where scarification rituals took place at puberty, suggesting that Nell was at least a young adult when she was abducted from Africa. One ad goes into detail about her clothing, describing each item she took with her. These details were intended to facilitate her capture. Today, they help create a portrait of Nell.

Historians can only speculate why Nell risked fleeing enslavement twice. The ads for her return are the only available clues to her motivation. The first ad, in March 1750, lists Nell’s age as “about 36,” old enough to have a partner or children she might be seeking. By 1753, the date of the second ad, Nell had been moved from New York City to rural New Jersey. This ad mentions the name and location of Nell’s previous enslaver, a detail which suggests that Nell might have family ties there. Without additional documentation, the portrait of Nell’s life remains incomplete.

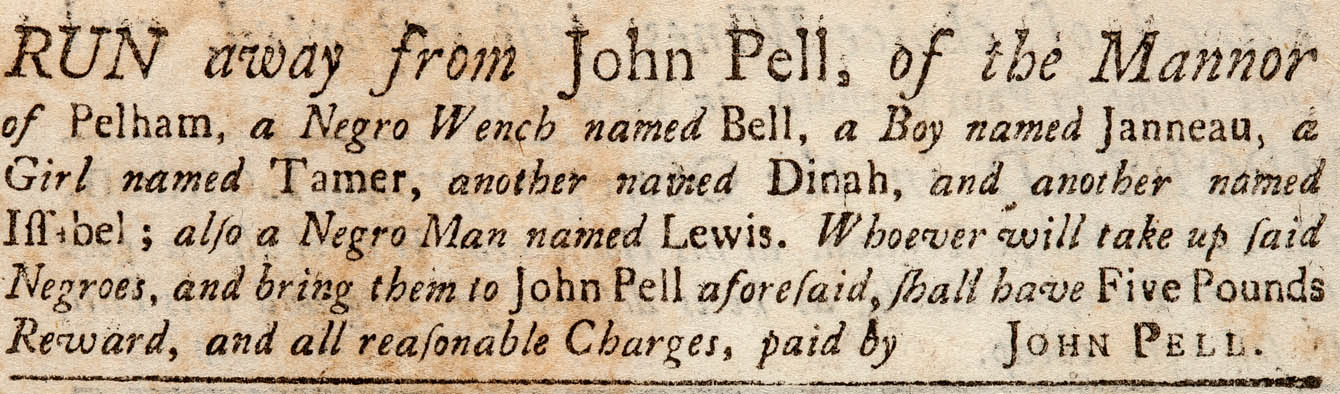

Most runaway ads list single individuals, suggesting that people fled on their own. This makes logistical sense, as it is easier for one person to run or hide than it is for a group. This November 1748 advertisement is less common. It describes a woman, Bell, a man, Lewis, and children Janneau, Tamar, Dianah, and Isabel. No family relationships (like parent or sibling) are listed, but the circumstance of their traveling together strongly suggests a family connection. No motivations or possible destinations are mentioned either. Perhaps the family feared being sold apart, like Joan and John Jackson, and chose to run away together instead.

The enslaved men Fortune, Venture, and Isaac ran away from coastal Connecticut along with a white indentured servant named Heday in spring 1754. Their timing corresponded with the planting season, suggesting a desire to do economic harm to an enslaver or to avoid harsh labor conditions. Since enslaved people were considered to be property by law, the act of running away constituted a theft of equipment. The ad also lists the supplies—including two boats—the men took with them.

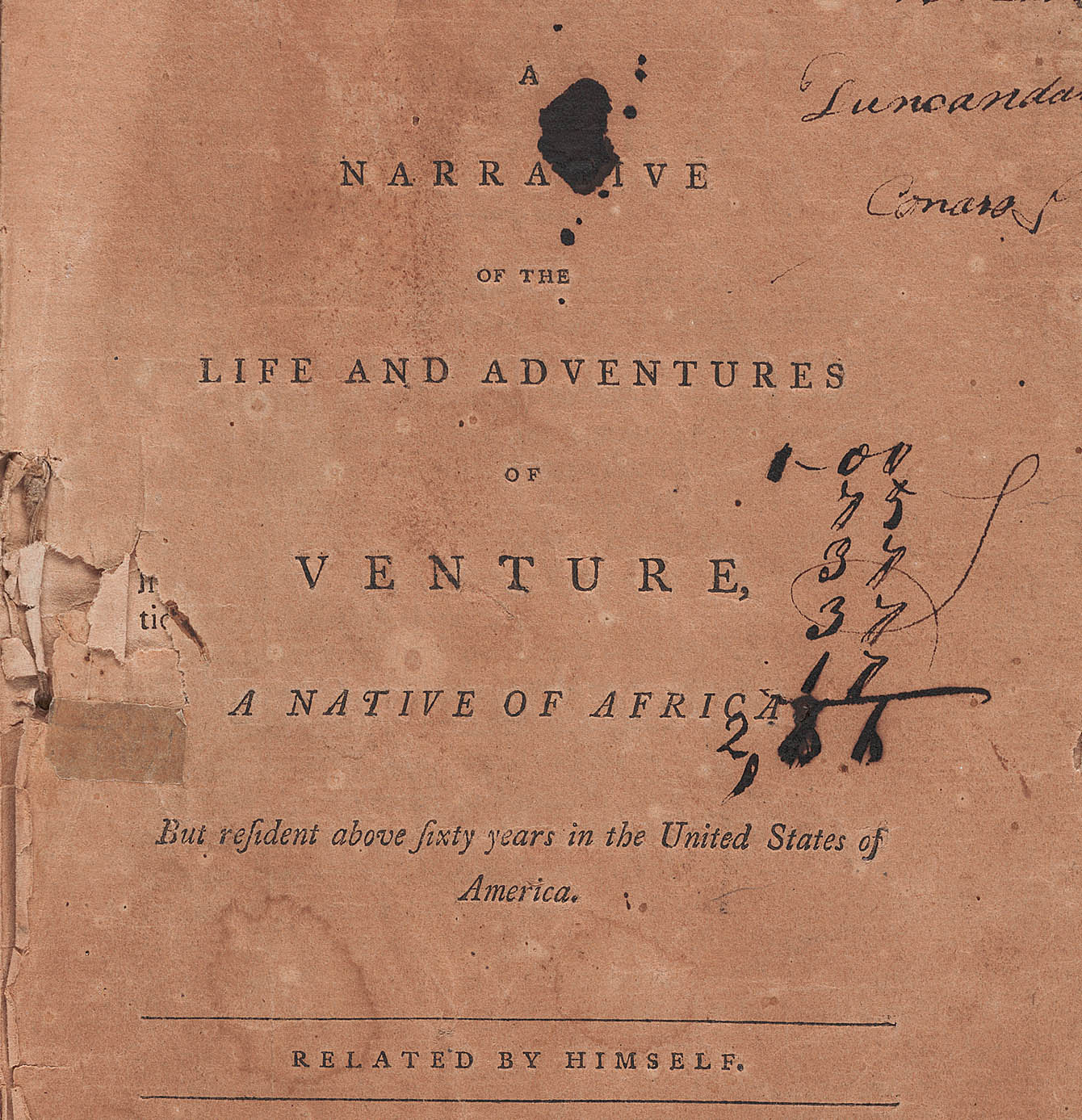

While the ad presents the enslaver’s perspective, Venture’s side of the story is also known, thanks to the autobiography he wrote after he purchased his freedom.

As a free man, Venture Smith wrote an autobiography that included an account of this escape. His narrative fills in the details that are missing from the runaway advertisement and provides insight into his motivation. After Heday attempted to abandon his fellow fugitives and abscond with the boat, Venture subdued him and returned him to Connecticut. While the advertisement only described his escape, Venture’s version included what happened after he returned.

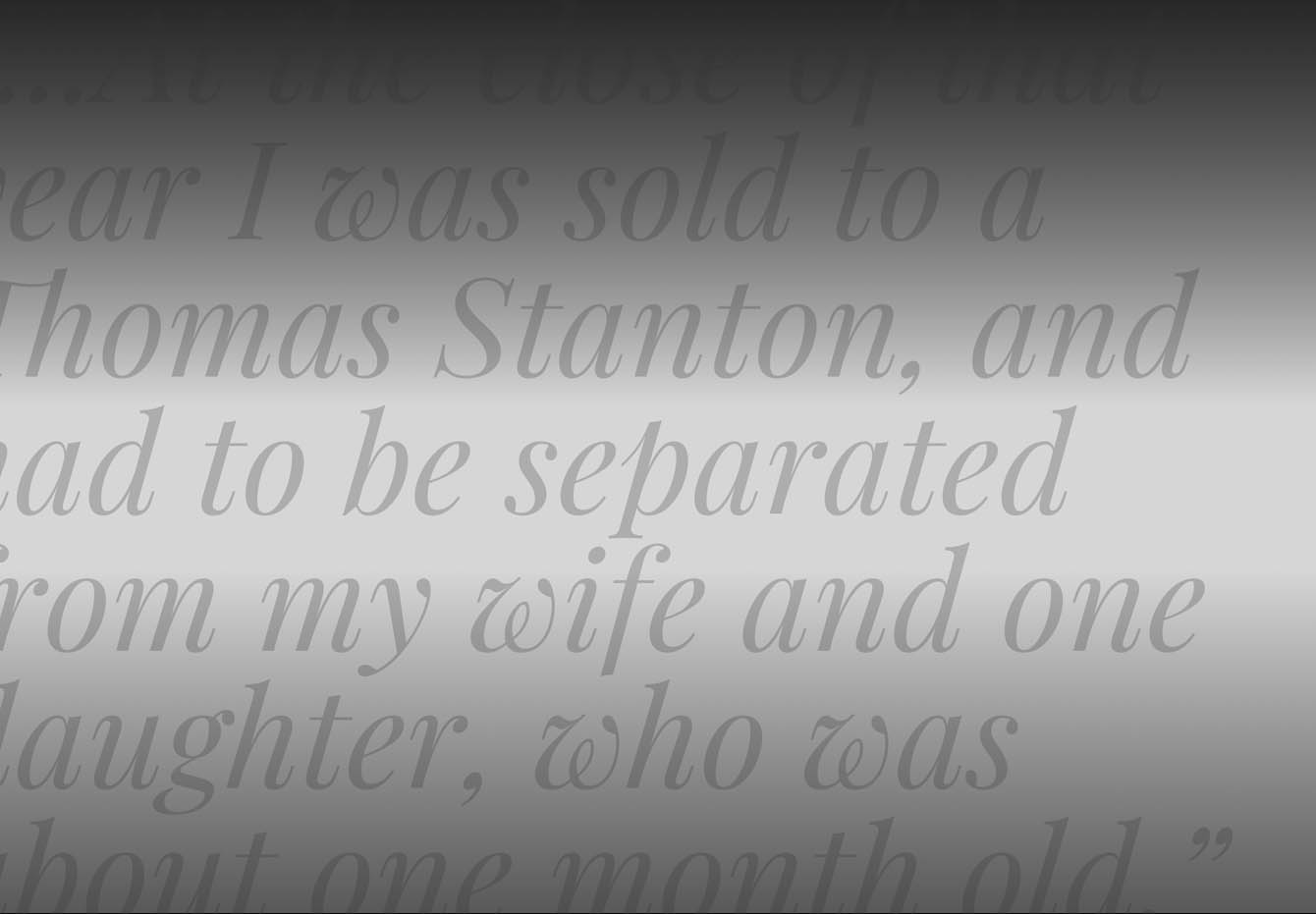

“I informed my master that Heddy was the ringleader of our revolt, and that he had used us ill. He immediately put Heddy into custody, and myself and companions were well received and went to work as usual…. At the close of that year I was sold to a Thomas Stanton, and had to be separated from my wife and one daughter, who was about one month old.”

Venture’s matter-of-fact retelling is a reminder that such acts of family separation happened to enslaved individuals every day.

Leather dresser John Breese’s ad for a fugitive named Galloway hints at complex relationships within New York’s enslaved community. The ad noted that Galloway was born in Albany and spoke Dutch. Being bilingual and familiar with the region, Galloway may have been entrusted with far-flung assignments. Such skills may also have helped him escape. He was described as being questioned at Colonel Philipse's mill in Yonkers, but allowed to continue because he claimed to be in pursuit of another runaway. For Galloway to have been believed, it must have seemed reasonable that he was given this responsibility.

Galloway’s story was further complicated because he claimed to be pursuing a “Cuba Man.” At the time the ad was published, England was at war with Spain. Mentioning a person of Spanish descent might have made Galloway’s story more believable. The reference to a “Cuba Man” also suggested that Galloway was involved in New York City’s 1741 insurrection conspiracy, as several “Spanish Negroes” were allegedly part of the plot. An enslaved man named Galloway was one of seven men executed on July 18, 1741, for their role in the conspiracy. Court transcripts noted that this man had formerly “belonged to a leather dresser.”